Recognition of Learning TOC

Key Highlights of this Brief

- Navigational help: Advisors play a critical frontline role in helping students navigate the PLA process.

- Informing all students: Institutions should prioritize PLA in messaging to all students.

- Methods that work for all students: Methods of PLA should be more inclusive of all learner experiences and preferences.

- Technology-enabled personalized advising: Effective advising about PLA should be technology-enabled, personalized, and easily understandable.

Introduction

Advising is a critical component of Prior Learning Assessment (PLA). Students may have a range of learning experiences that advisors can help translate into academic credit. Adult learners – defined here as undergraduate students who are 25 years and older and have either no college credit or some college credit but no degree – may especially benefit from PLA and PLA advising. Such students may arrive at an institution with college-level knowledge acquired through military or occupational training, unaware of PLA credit options available to them. Academic advisors have the opportunity to directly connect with students and provide tailored information to support them on their path toward credential attainment. Maximizing the potential benefits of PLA requires advisors to clearly understand and advise students on how to effectively navigate the process.

Redesigning advising systems is a key part of the work that NASPA – Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education and core partner organizations are leading as part of the Advising Success Network. Rethinking systems of advising raises questions about advisor perspectives and strategies around PLA. NASPA’s engagement with advising experts, emphasis on the value of learning outside the classroom, and commitment to supporting a changing student population prompts exploration of the future direction of the field.

The mission of the Advising Success Network (advisingsuccessnetwork.org), supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, is to help institutions build a culture of student success, with a focus on students from low-income backgrounds and students of color, by identifying, building, and scaling equitable and holistic advising solutions that support all facets of the student experience.

Another solution-driven network of organizations funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Every Learner Everywhere (everylearnereverywhere.org) is facilitated by the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education and its digital learning unit, WCET (wcet.wiche.testing.brossgroup.com). The mission of Every Learner Everywhere is to help institutions use new technology to innovate teaching and learning, with the goal of improving student outcomes—especially those of first-generation college students, low-income students, and students of color.

Background

To examine the conditions around advising students about PLA and the current state of the field, NASPA conducted a research study involving: 1) video and phone interviews with practitioners in advising roles at institutions, and 2) a national survey of student affairs professionals. NASPA’s research findings help address the following core research questions:

- To what extent are shifts in higher education impacting advising practices related to PLA?

- In what ways are advisors helping students navigate the PLA process?

- What do advisors perceive as key student challenges related to PLA and how are they addressing them?

We first describe the research methods used to address these questions. Then, drawing from research findings, this brief unfolds in four sections: i) current trends in advising, ii) advisor perspectives, iii) student needs, and iv) opportunities for collaboration and coordination. We end by offering several recommendations for practice based on our findings.

Methodology

Interview questions covered several dimensions of PLA and advising that helped inform the development of a national survey instrument. The survey was sent to NASPA members with academic advising in their job title or listed in their profiles as one of their functional areas.

Types of Prior Learning Assessment

For the purposes of NASPA’s survey, PLA includes assessment of a student’s prior learning for credit in any of the following ways:

- National standardized examinations that test students’ level of knowledge about a subject. Typical examinations include the College Level Examination Program (CLEP), Advanced Placement (AP), International Baccalaureate (IB) Diploma Program, and DANTES Subject Standardized Test (DSST) Credit by Exam Program.

- Pre-evaluations of military or professional learning by the American Council on Education (ACE) or the National College Credit Recommendation Service (NCCRS). These third-party evaluation providers present credit recommendations for formal courses, certifications, and trainings offered by the military and/or in professional organizations.

- Institution-led challenge exams developed and administered by academic departments or faculty to assess learning.

- Individualized student portfolios that serve as verified records that document a student’s collection of learning experiences.

- Internally evaluated external credit for student learning at a non-accredited institution. Institutions may have different standards or policies for accepting transfer credit from non-regionally accredited institutions, certifications, licenses, or international institutions.

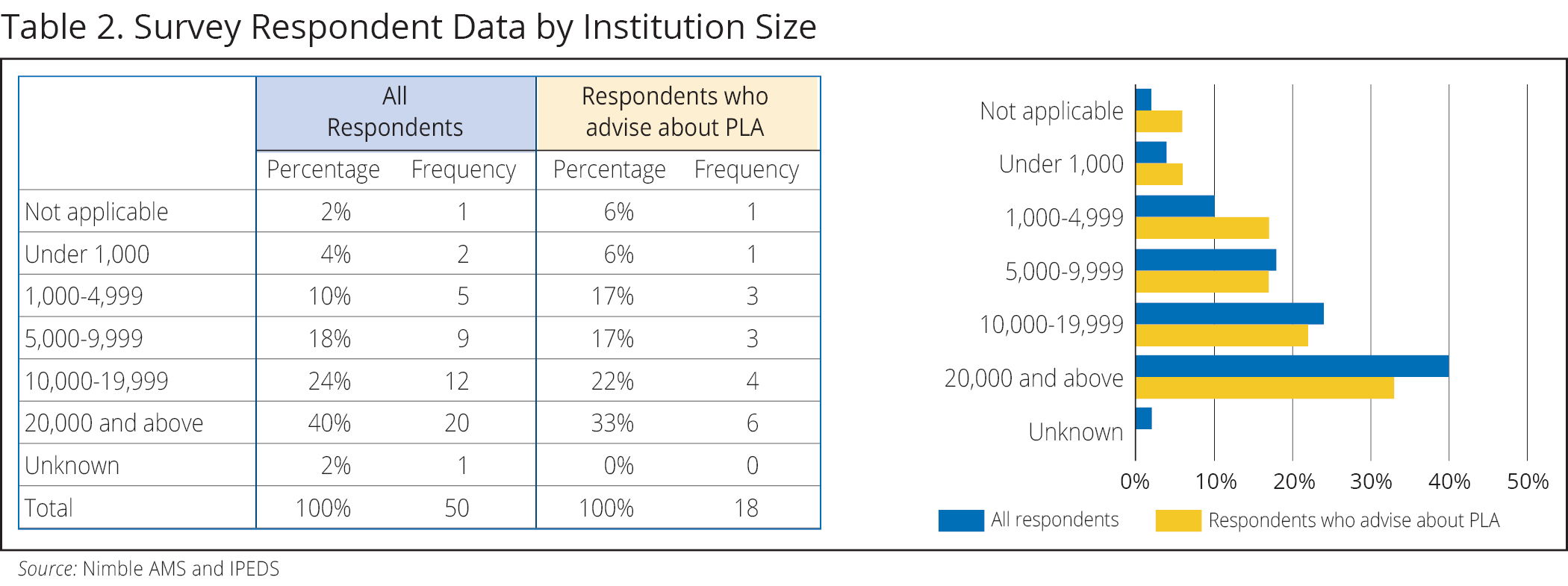

At the close of the survey, NASPA received 50 submissions. Approximately one-third of total respondents were able to speak to most survey questions, due to the narrow subset of respondents that self-identified as administrators who advise undergraduate students about PLA (see Tables 1 and 2). Despite a small sample size, several key themes emerged from responses to open-ended survey questions that align with insights drawn from interview data. Because of the small sample size, findings in the following sections are not differentiated by institution sector/control.

Findings

Current Trends in Advising

As college students navigate a higher education landscape that is becoming increasingly complex and filled with options for earning a credential, the role of advisors is more critical than ever. Professional advising is an essential function for institutions of higher education, as students are making decisions across myriad components of their educational journey. For example, it is common for students to balance choices that will impact their financial stability, academic progress, social integration, and post-college career. Many choices will require students to decipher unfamiliar information, use complex processes, and take actions on short timelines. As a result, the role of an advisor is invaluable to students as they make decisions that will impact their progress. Institutions are re-examining their delivery of advising support with a focus on several key areas: multiple advising models, technology use, personnel shifts, and the integration of different types of advising. It is especially important that each of these areas be properly addressed to deliver high-quality advising experiences for adult learners seeking credit for prior learning.

Multiple models

Institutions have provided advising services to students for decades. The structures and processes by which advising resources are delivered, however, continue to evolve. For example, many campuses are considering centralized versus decentralized approaches.

A centralized structure offers students the benefit of accessing multiple forms of assistance from a single, highly visible location on campus. Centralized advising structures take a streamlined approach and are most frequently used by two-year public institutions.[1] Having an advising office centrally located near other offices and student services can increase accessibility for students balancing other priorities and who have limited time available to spend on campus. Such a model often involves advisors providing support across multiple areas, which could help adult learners understand the impact of applying for PLA credit. For instance, an advisor who is knowledgeable of PLA and working in a centralized model could explain the impact on a student’s time to complete a credential and overall tuition cost.

A decentralized approach could be beneficial since the advisor in such models is often a faculty member in the student’s field of study. A decentralized model can help adult learners who seek PLA credit because the advisor may have more thorough knowledge of the student’s major. In an ideal scenario, adult learners would be able to access advice in a blended format, one that leverages the expertise of several professionals who are knowledgeable of their completion plan and who are highly accessible.

Regardless of the organizational structure by which advising services are provided, institutions need to ensure that PLA-related information is delivered consistently. This may be easier in a centralized model, particularly in instances when proactive outreach or training is limited. If proactive outreach or training is limited, then − at the very least− institutions should have a centralized site to disseminate information to advisors regarding PLA options and policies.

Technology Use

Most institutions that aim to provide a high-quality advising experience leverage technology to perform a variety of functions that help advance student persistence and completion outcomes. Campus investments in technology range from large-scale systems with multiple features and users, to tailored tools designed with specific functions in mind. Institutions may use technology to create counseling systems that promote student connections to support services; education planning systems for mapping degree plans, streamlining scheduling appointments, and tracking degree completion progress; or intervention systems that identify students who are struggling academically and may need more proactive engagements.[2] While technology can improve process efficiencies and potentially decrease advisor caseloads, it does not necessarily mean that fewer staff are needed to fulfill advising responsibilities. As a result, technology investments are sometimes one of the more expensive aspects of advising, and this has implications for institutions’ capacity to sustain their advising model.

It is also important for institutions to implement a change management system to ensure effective technology use. Specifically, training, communication, and evaluation policies and processes are needed to support advisors and empower them to use technology effectively. For example, EDUCAUSE released a guide to help institutions that participated in the Integrated Planning and Advising for Student Success (iPASS) project, a national initiative to help institutions increase their capacity to deliver technology-enabled advising.[3] If institutions can use technology effectively, it is possible to reach more students and provide the real-time support they need to thrive. If used ineffectively, technology can create a barrier for students who do not fully understand their options. This is especially important for adult learners who have college-level learning and are trying to determine how to apply for PLA credit or determining the best pathway to apply their PLA credits.

One interviewee pointed to the need for proactive outreach to identify students most likely to be eligible for PLA:

“The most successful model has been where there is an advisor that has been a key point person and there is a routine in place to take students for whom you might expect have some prior learning that could be examined, and make sure all those students are invited to connect and meet with that advisor.”

Specifically, a flexible, routinely updated degree audit system can serve as a critical planning tool for advisors to help students assess the impact of prior learning credit on possible pathways to completion. Technology here can enable advisors to better personalize sessions and identify opportunities where prior credit can fill gaps in course requirements.

As advisors use online degree planning tools to inform discussions with students about progress toward completing a credential, it is essential that they receive training and can effectively navigate multiple technology systems in various contexts.

Personnel Shifts

Institutions often face the common challenge of managing high advisor turnover rates. Although advisors can use technology to alleviate some of the burden of completing tasks manually, the resulting time efficiency is often reallocated to increase their number of advising appointments. As a result, many advisors manage high caseloads and a pace of work that is difficult to sustain long term.

The National Academic Advising Association (NACADA) suggests that one way institutions can address increasing caseloads and large student-to-advisor ratios is to provide intentional career ladder opportunities.[4] By creating a career ladder, institutions can help avoid the perception that an advisor has limited opportunities for upward mobility. A career ladder can also help senior leaders identify the areas for which more advanced-level advising expertise is needed and structure the advising model appropriately. For example, while NASPA’s research on advisors revealed ample instances of campuses using robust strategies for addressing the needs of adult learners, few of those approaches were combined with a specific focus on leveraging PLA. As advisors advance in their careers, another specialized role could involve engaging in professional training to build expertise about PLA opportunities and alignment with experiences of adult learners. Becoming an expert about PLA opportunities may serve as another step on a structured career ladder for advisors.

Integration

Institutions that have a goal of improving postsecondary attainment and economic opportunity for their graduates must have a systematic approach for addressing myriad factors that impact student persistence and completion.[5] Institutions are becoming increasingly aware of the complexity of adult learners’ routine college decisions. Adult learners are often balancing multiple responsibilities and competing priorities. Approximately 62 percent of undergraduates, many of whom are adults, work while in school on a full- or part-time basis, and 28 percent have children.[6] With tight schedules and various living expenses to manage, time to degree, flexibility, and affordability serve as important factors influencing adult learner decisions about higher education.[7] For example, a decision to enroll in a certain program may hinge on an individual’s perception about whether the coursework is relevant to their career goals, and if the financial and time requirements would still allow them to meet existing obligations.

Literature about models of adult learning may also inform advising strategies. According to Donaldson and Graham’s Model of College Outcomes for Adult Learners, there are six key elements that affect adult undergraduate students’ learning and experiences in college:

- prior experiences,

- orienting frameworks such as motivation, self-confidence, and value system,

- adult’s cognition or the declarative, procedural, and self-regulating knowledge structures and processes,

- the “connecting classroom” as the central avenue for social engagement and for negotiating meaning for learning,

- the life-world environment and the concurrent work family, and community settings, and

- the different types and levels of learning outcomes experienced by adults.[8]

Understanding an adult learner as a whole person is one way to apply this model and is a defining characteristic of holistic advising.[9]

Many campuses are increasing their emphasis on delivering a holistic and integrated advising experience. As mentioned earlier, the span of students’ decisions requires advisors to be knowledgeable about multiple and varying academic, financial, and career options. An integrated PLA advising experience would also include the professional having a thorough understanding of the source of prior learning credit and how it can be applied. Similar to the reference to a centralized model, a student would be served well by working with an advisor who is connected to professionals in other offices of the campus, such as the continuing education office, academic dean’s office, and financial aid. The extent to which an institution’s advising process is integrated and holistic will help ensure adult learners’ full understanding of their options and successful degree completion.[10]

Advisor Perspectives

Advising structures, policies, and practices around PLA can vary considerably across institutions and departmental programs. Some institutions may have only one or two departments that accept credit for prior learning, while others may have campus-wide policies about PLA and invest in capacity building efforts to improve advisor, staff, faculty, and student awareness.

Differences in campus contexts and advising models impact the way PLA is administered. One interviewee explained that very large institutions may operate in silos, often resulting in the policies and processes for PLA in one department to differ from those in another department. Another interviewee said that their institution has advisors who all know the fundamentals of PLA but ultimately funnel related questions, information, and students to a single individual who has a deeper set of knowledge about the process. Here, the primary point of contact is responsible for organizing, overseeing, and processing all the paperwork about PLA and also teaches the students to create prior learning portfolios. Alternatively, an institution may have advisors who work with students across all the majors that the university offers, requiring them to be well-versed about how prior learning credit might fit relative to the design of different curricula.

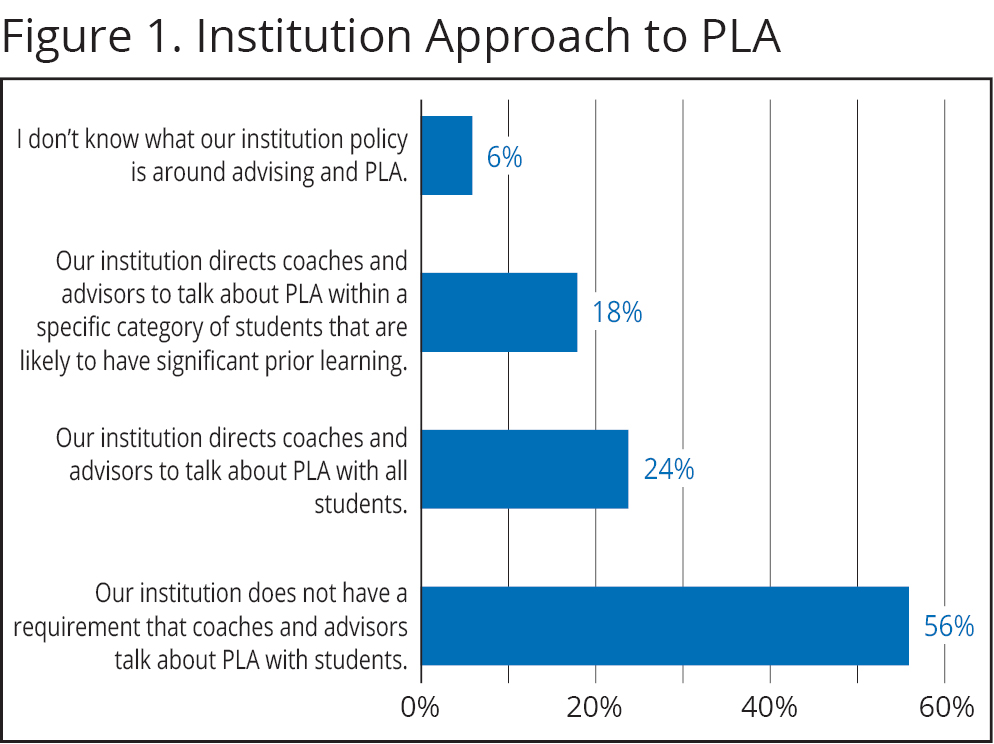

Institutional philosophy about PLA may impact the robustness of advising-related policy and support systems for students. Figure 1 illustrates which statement respondents selected as most accurately describing their institution’s approach to PLA. More than half of respondents said that their institution does not require coaches and advisors to talk about PLA with students. While survey data also indicate that most respondents do have occasional conversations with students about PLA, lack of formal policies in place to encourage proactive communication may suggest that PLA is not a high priority for the institution, and that only a few professionals on a campus are knowledgeable about it.[11]

Research findings also reveal common threads about the way advisors perceive their role and the value of PLA. Among the offices that may be involved on some level with PLA at an institution, advisors often serve as the front-line administrators responsible for helping students navigate the process. Interview and survey data suggest that effective advisors should have some capacity to translate legalese and policies set by the institution and program chairs into accessible language that resonates with students. For example, advisors may find themselves responsible for explaining the distinction between years of experience and college-level learning. Some institutions or faculty members may feel that the pedagogy of a certain program does not allow for certain courses to be replaced with prior learning credits. One interviewee highlighted the difficulty of explaining to a student with 30 years of marketing experience that they were not able to get credit for a basic-level marketing course credit that would go toward their major. This interviewee expressed the challenge this poses for advisors to offer rationale for such a decision that is not in their control or traditional area of expertise:

“It’s hard for the student to understand that. We’re the messenger. We end up being that person who has to explain it, when a lot of times we’re not faculty first. We’re the student affairs professionals first. We’re the warm and fuzzy and beer and pizza.”

An interviewee noted that students often have a misconception that they should get credit for years of work experience rather than the knowledge that they learned from the work experience.

Encouraging students to reflect on their experiences more closely can empower them to take ownership over their learning and draw connections with their future career goals. In cases when a PLA option is not available to a student, one survey respondent said that their staff apply a more career-oriented lens to the conversation and discuss how students can present their experiences for future professional application.

In addition to explaining information to students, advisors may also need to serve as translators on behalf of students as they advocate to leadership and faculty about the value of PLA. Survey data reveal that the majority of survey respondents believe that the PLA process can have multiple benefits for students, recognizing that it saves students time and money, motivates them to start or complete college, and encourages connections across learning experiences. Some learning experiences may not clearly map back to articulation tables or nationally recognized credit equivalences, which leaves advisors responsible for identifying possible connections in the gray area. Some faculty may resist giving students course credit for college-level learning gained from past experience due to perceptions that students can only learn the material through an in-classroom experience. An interviewee shared how this thinking does not make sense for adult learners who only take courses online and can demonstrate equivalent knowledge through a portfolio. Advisors need to know how to make the case to faculty or department chairs about a student’s level of knowledge gained from past learning experiences and the value of PLA.

Advisors can help make the case for PLA to faculty and staff by pointing them to data from the institution. They can also highlight student success stories and share data and resources from this initiative (wiche.testing.brossgroup.com/recognition-of-learning), to name a few.

Student Needs

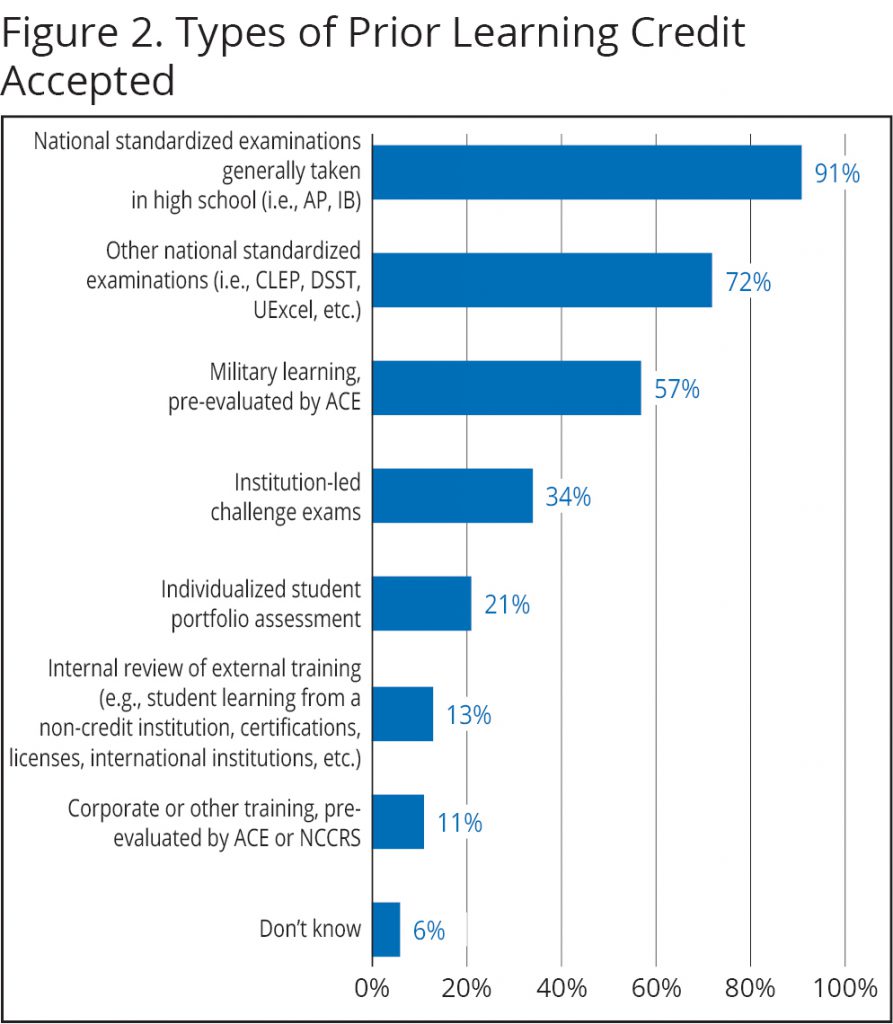

A common challenge that advisors identified in the survey response data is the lack of PLA opportunities geared toward adult learner experiences. Figure 2 highlights the range of prior learning credit opportunities accepted at respondent institutions. When asked to select all types of PLA opportunities for credit accepted, most respondents selected national standardized examinations generally taken in high school (91 percent) or other national standardized examinations (72 percent).

Patterns of open-ended responses in the survey reinforce this finding. For example, one respondent stated that a majority of their institution’s students are adults, but that their PLA options are “extremely limited” to credit by exam options that may require students to pay out-of-pocket costs. There is opportunity for greater diversification of PLA opportunities for students, and more can be done to align PLA opportunities, processes, and policies with the needs of adult learners. Having strong buy-in across the institution about the importance of PLA for adult learners is needed in order to improve the experience for students. One interviewee highlighted the need to embrace inclusive thinking about learning:

“Every student that comes to us is not a blank slate. Every student comes to us with learning, no matter the age. Our older adult students will have learning from professional experiences or professional non-credit training or some other elements, and when we talk about equity and we think about the value of perspectives that all students bring into our institution [prior learning] ought to be recognized.”

Without a shift in institutional philosophy about what counts as learning, advisors find that only certain types of students – namely traditional college-age students who earned IB or AP credit from courses in high school – tend to have their learning recognized. Several research studies have identified racial and socioeconomic disparities in pre-college access and participation in dual enrollment, AP, and IB opportunities.[12] These methods of PLA tend to disproportionately benefit students who are White and students who are in low-minority and low-poverty high schools, leaving students of color and those attending high-minority and high-poverty high schools without the same opportunities to earn college credit for college-level learning outside the classroom.

Additionally, adult learners may have varying levels of comfort with the multiple-choice format of CLEP, DSST, or departmental exams, and might be better prepared to demonstrate mastery of learning through a portfolio review.[13] Conversely, another survey respondent pointed out that the time required for a portfolio preparation course can pose an access barrier for some students. Adult learners may face demanding work schedules and other obligations that prevent them from taking a portfolio preparation or development course. While guidance about key components to include in a portfolio is helpful, some students may benefit from alternative supports and resources offered online that are more flexible with their schedules.

Several survey participants raised concern about the need for stronger outreach efforts to increase student awareness about PLA. One survey respondent explained that students may not know there are PLA options available and do not know the right questions to ask. Another survey respondent echoed this point by comparing their institution’s limited access to PLA to “a secret club,” adding that more could be done to make the process more welcoming for students. Some students may have heard of PLA but come to advisors not knowing how to actualize its benefits. Survey data suggests that students may have previously received information about PLA prior to advising sessions, but they have no understanding how it applies to them or the requirements for their program of study.

Advisors Can Help Students Earn Credit for Prior Learning

Below is a summary of a student experience shared with interviewers as part of a parallel research effort in this series of briefs.[14]

Clara wanted to go to college because, as she put it, she did not want to be a waitress for the rest of her life. She attended a local community college in a large Midwestern city, first majoring in architecture before switching to a dental assistant program. She discovered she liked healthcare but did not want to work as a dental assistant. So, her college advisor suggested that Clara study Healthcare Business Services, which is where Clara found her passion for helping patients through financial advocacy. The first in her family to graduate from college, Clara is 24 years old and currently works as a financial advocate for uninsured pregnant women who are patients at a women’s healthcare clinic affiliated with the local hospital.

Clara paid her way through college by working two jobs − a waitress and patient advocate at the local hospital. During her time as a patient advocate, she worked in the hospital registration department, the emergency room, and on inpatient floors, where she learned a lot about the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), insurance, plus hospital and medical terminology. Toward the end of college, Clara met with her advisor once again, this time to discuss the final courses she needed to graduate. Clara’s advisor knew that she had experience working in a hospital and suggested that Clara meet with another advisor who specialized in PLA so that she could potentially obtain credit for that experience. The PLA advisor explained the process of earning prior credit by creating a portfolio, which included activities such as submitting a resume and cover letter, and writing essays addressing things related to learning in course equivalents.

By completing this process, Clara was able to save money, save time by not having to attend courses covering material she already knew, and graduate from college a semester early. Without her advisor taking the time to get to know Clara beyond her academics, she might not have known that Clara was working in the hospital and eligible to opt out of two courses for her major by completing a portfolio. Without her advisor informing Clara of this opportunity and connecting Clara to the PLA advisor, Clara might not have ever learned this was an option. This example clearly shows the positive ways in which college advisors can support their students in learning about and taking advantage of opportunities to earn credit for prior learning.

Opportunity for Collaboration and Coordination

Achieving an effective PLA experience for students can hinge on the extent to which advisors, faculty, and staff across the institution regularly coordinate and share information. One interviewee emphasized the importance of having an advisor who can serve as a liaison with faculty and facilitate routine discussions about updates to curricular formats. Another interviewee spoke to the need for support from the registrar:

“Your registrar approval and support are probably the most important thing, besides that of your provost or your higher-up administration. Without those, it’s very hard to push through prior learning. You have to have the administrators on board, and they have to be willing to find a way to articulate it on a transcript.”

Including key stakeholders early on in discussions with professional advisors about PLA routines and policies can help establish authentic connections and shared understanding about approaches. Cross-functional teams could be formed to continuously review processes and create a more seamless experience for students.

Another interviewee identified having “an open line of communication” as an important element of advising when it comes to PLA, given the need for frequent approval from department chairs or faculty directors to determine if a prior learning experience can be accepted and counted toward a major. Without coordination, one interviewee explained how frustrating the process can be for students when they must talk to multiple people before finally being directed to the one who can answer their questions. Frequent engagement with department chairs can help advisors accurately identify who can best address certain issues or student questions.

Collaboration across an institution and coordination of information can help ensure that students receive accurate, consistent information. When asked who advises or supports students regarding their PLA options, most survey respondents indicated that students interact with multiple constituents on campus, primarily during academic advising sessions, enrollment, orientation, and through their faculty or departments. Gaps in staff and faculty awareness and understanding regarding PLA definitions and where it can be applied can lead to inconsistent advising about available options. Survey data indicate that a third of respondents feel that their understanding about evaluating prior learning assessment depends on the type of assessment, and a quarter indicated that their understanding is limited to how it applies to a specific college/department. Without a shared awareness and education about PLA across the institution, students may be inadvertently given misleading or conflicting information.

Recommendations for Practice

The research findings suggest that institutions may have only a few advising professionals responsible for providing PLA-related guidance to undergraduate students. This could result in more students being unaware of their options for earning PLA credit and the process for pursuing it. It is possible that as institutions continue to manage advising priorities, hiring more staff who are knowledgeable about PLA may not be fiscally possible, especially now due to the economic impact of COVID-19. However, the research led to three recommendations that colleges can pursue with existing resources:

- Develop formal PLA-related processes and policies that include an evaluation component.

- Provide additional PLA-related training and professional development.

- Proactively connect with students to gather information and to refine PLA practices.

Develop formal processes and policies for how to award PLA credit, including a process for evaluating such policies.

Interviews with advisors suggest that the methods by which institutions manage PLA-related advising in many cases could be improved with more documentation and periodic updates and reviews. Some interviewees pointed to the lack of information regarding PLA on their campus; others suggested that comprehensive information about PLA options exist in an online catalogue, website, or other form of communication that is available to students and all staff. One interviewee even identified a “how-to guide” as an element of an effective advising process: “My institution has clear how-to guides that ensure students know their expectations. There is also a faculty approval committee and policy in place to review prior learning portfolios.” In addition to ensuring information regarding PLA is widely available on campus, advising offices could create a document to serve as a guide and provide answers to a set of frequently asked PLA questions.

“My institution has clear how-to guides that ensure students know their expectations. There is also a faculty approval committee and policy in place to review prior learning portfolios.”

An evaluation component needs to be included in the policies that are developed around PLA. Just having the policy does not go far enough – institutions need to see if the policy/practices are actually having an impact. Advisors can also periodically review formal practices and provide feedback to faculty, registrars, and other campus partners as necessary to consistently address students’ needs. Similarly, advisors can and should be part of the feedback process on policy effectiveness: they are in a unique position to provide evidence-based information back to faculty and administrators on student perceptions and reactions to policies.

Having resources with specific, institution-wide guidance and policies can help advisors clearly discern what can and cannot be recognized for credit. Advisors can reference such resources during sessions with students, and they could include it during regular meetings with faculty or others on campus. Additionally, some institutions may keep records of course equivalency decisions in a central database, which can simplify the process for future students in repeat situations and give advisors greater clarity about potential questions. Institutions can also better ensure that all students who pursue the credit can receive a similar experience.

Provide additional PLA-related training and other professional development for faculty, staff, and administrators.

By offering PLA-related training and professional development to a broad number of professionals across the campus, institutions can increase the likelihood that students will experience fewer difficulties in navigating the process. This would be especially helpful for adult learners, some of whom spend less time on campus and need to maximize their meetings with advisors. Interviews suggest that guidance from a comprehensive training resource would be helpful.

“A prior learning assessment toolkit for higher education professionals would be useful. The standardization of prior learning as a tool to diversify the learning environment would also be helpful.”

Professional membership associations – such as NASPA and the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers (AACRAO) – and other national organizations are in a good position to assist with the creation and distribution of such resources. National- or state-level resources could be shared by these organizations to help promote widespread awareness of promising practice. In addition to providing training and insights about the landscape of advising trends and issues, staff at these organizations can provide opportunities for advisors to connect and share effective strategies. With or without external resources, institutions are still left to reflect on current processes and identify what training elements should be advanced or receive additional focus.

Proactively connect with students to gather information and refine PLA practices.

Students benefit from personalized, proactive guidance from their advisors about PLA options that best fit their needs and preferences. Research suggests that there is an opportunity for advisors to engage in early assessment efforts to identify options for prior learning credit that might be available to students. There should be a routine in place to identify students who might be expected to have some prior learning, perhaps through indicators like military-connected backgrounds, professional experience, or prior enrollment in a postsecondary institution. Advisors could proactively invite those students to meet to discuss how their past experiences might connect to their academic majors. Having those early conversations can help advisors extract general information and determine whether a portfolio, departmental exam, or other assessment is best suited for each student.

Adult learners would be an excellent group for advisors to consult, as their perspective would help identify areas for improvement. Surveys, focus groups, and other data collection activities can provide advisors with the needed feedback to create clear and manageable processes. In preparation for student interactions, advisors may find it useful to engage in a process-mapping exercise. Such an exercise would involve the development of a flow chart that describes, in as many details as possible, each step that a student would need to take to successfully pursue PLA credit.

Conclusion

It is important for colleges and universities to proactively and carefully plan for providing holistic supports to students, which includes recognizing the value of the diverse life experiences that students already have when arriving on campus. There is a need for advising, campus mission and institutional culture to move toward supporting the multiple needs of students.[15] This is especially relevant to students who pursue PLA credit, as they will require a well-organized system that is easy to navigate. Although this examination of how the advising function connects to PLA supports was limited by the low number of advisors who work both with adult learners and focus on PLA, pre-survey interviews with advising professionals revealed that few, if any, institutions had an advising function with a designated person for both roles.

Despite the limited number of respondents, the responses highlighted several PLA-related areas for which additional research is needed. Advisors described interest in knowing more about the larger community of professionals who are engaged in PLA work and approaches for evaluating the impact of PLA. As a result, three areas for additional research emerged: identifying common scenarios in which PLA credit is awarded; analyzing how, on a national level, institutions are incorporating PLA in their routine procedures and operationalizing a focus on equity; and comparing the performance of students who have PLA credit with those who do not. In addressing each of these areas of future research, the authors advocate for a larger sample so that results can be disaggregated by institution sector. In the absence of additional research, colleges should consider connecting with peer institutions and national organizations to stay abreast of current trends.

The current COVID-19-related economic condition suggests there will be more opportunities to engage displaced workers in postsecondary education as they look to reskill and upskill. Recent research continues to demonstrate that PLA is a powerful tool that can help get students what they need faster and cheaper.[16] As this brief shows, advisors can and should play a key role in this. The recommendations included in this brief can support professionals who strive to help students complete a credential with PLA credit.

Endnotes

[1] Celeste Pardee, “Organizational Models for Advising,” NACADA Clearinghouse of Academic Advising Resources, 2004, accessed on 28 July 2020 at https://nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Clearinghouse/View-Articles/Organizational-Models-for-Advising.aspx

[2] Hoori S. Kalamkarian, Melinda M. Karp, & Elizabeth Ganga, What We Know About Technology-Mediated Advising Reform, (New York, NY: Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University, February 2017), accessed on 29 July 2020 at https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/what-we-know-technology-mediated-advising-reform.html

[3] EDUCAUSE, Planning for Rollout and Adoption: A Guide for iPASS Institutions (Washington, DC: EDUCAUSE, 27 January 2017), accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://library.educause.edu/resources/2017/1/planning-for-rollout-and-adoption-a-guide-for-ipass-institutions.

[4] Cindy Iten and Albert Matheny, “Promoting Academic Advisors: Using a Career Ladder to Foster Professional Development at your Institution,” Academic Advising Today 31, no. 3 (2008), accessed on 1 July 2020 at https://nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Academic-Advising-Today/View-Articles/Promoting-Academic-Advisors-Using-a-Career-Ladder-to-Foster-Professional-Development-at-Your-Institution.aspx.

[5] Achieving the Dream, Holistic Student Supports Redesign: A Toolkit for Redesigning Advising and Student Services to Effectively Support Every Student (Silver Spring, MD: Achieving the Dream, October 2018), accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://www.achievingthedream.org/sites/default/files/resources/atd_hss_redesign_toolkit_2018.pdf.

[6] Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Postsecondary Success, “Today’s College Students Infographic,” accessed on 9 January 2020 at https://postsecondary.gatesfoundation.org/areas-of-focus/our-policy-advocacy/advocacy-priorities/america-100-college-students/.

[7] Dennis S. Lettman, “Identifying What’s Important for Adult Learners,” The Evolllution, 18 January 2013, accessed on 9 January 2020 at https://evolllution.com/programming/program_planning/identifying-whats-important-for-adult-learners/.

[8] Joe Donaldson and Steve Graham, “Model of College Outcomes for Adults,” Adult Education Quarterly, 50, no. 1 (November 1999), accessed on 3 August 2020 at http://aeq.sagepub.com/content/50/1/24.full.pdf

[9] Stacey M. Kardash, “Holistic Advising,” NACADA Academic Advising Today, 26 May 2020, accessed on 3 August 2020 at https://nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Academic-Advising-Today/View-Articles/Holistic-Advising.aspx. Beth Giroir and Jeremy Schwehm, “Implementing Intrusive Advising Principles for Adult Learners in Online Programs,” NACADA Clearinghouse Resource, 24 April 2014, accessed on 3 August 2020 at https://nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Clearinghouse/View-Articles/Implementing-Intrusive-Advising-Principles-for-Adult-Learners-in-Online-Programs.aspx

[10] Giroir and Schwehm, “Implementing Intrusive Advising”. Tyton Partners, Driving Toward a Degree: Collaboration is Crucial to Holistic Student Supports, (Washington, D.C.: NASPA Advising Success Network, 21 May 2020), accessed on 3 August 2020 at https://www.advisingsuccessnetwork.org/foundational-context-and-planning/collaboration-is-crucial-to-holistic-student-supports-drivetodegree/

[11] Wendy, Kilgore, An Examination of Prior Learning Assessment Policy and Practice as Experienced by Academic Records Professionals and Students (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, July 2020), accessed on 28 July 2020 at https://wiche.testing.brossgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/aacrao-brief071420.pdf; Council for Adult and Experiential Learning and Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, The Boost from PLA. Leibrandt.

[12] U.S. Government Accountability Office, Public High Schools with More Students in Poverty and Smaller Schools Provide Fewer Academic Offerings to Prepare for College (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Accountability Office, GAO-19-8, 2018), accessed on 9 January 2020 at https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/694961.pdf; Todd Kettler and Luke Hurst, “Advanced Academic Participation: A Longitudinal Analysis of Ethnicity Gaps in Suburban Schools,” Journal for the Education of the Gifted 40, no. 1 (February 2017): 3-19, accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353216686217; Christina Theokas and Reid Saaris, Finding America’s Missing AP and IB Students (Washington, D.C.: Education Trust, June 2013), accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Missing_Students.pdf; John Fink, “How Does Access to Dual Enrollment and Advanced Placement Vary by Race and Gender Across States?,” Community College Research Center, The Mixed Methods Blog, 5 November 2018, accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/easyblog/access-dual-enrollment-advanced-placement-race-gender.html.

[13] For example, one of the adult learners interviewed as part of the research conducted by CAEL and WICHE reported, “I mean I’d heard of like CLEP tests and things like that, but… I don’t test, I just, I’m a mess when it comes to tests. So, to go into something like that, that made me very fearful. But bringing a portfolio into it and being able to hands on put together what you know and show, that was great for me.” For more information, see Council for Adult and Experiential Learning and Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, The Boost from PLA: Results from a Targeted Study of Adult Student Outcomes, (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education), forthcoming and Sarah Leibrandt, PLA from the Student’s Perspective: Lessons Learned from Survey and Interview Data, (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education), forthcoming.

[14] Council for Adult and Experiential Learning and Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, The Boost from PLA. Leibrandt, PLA from the Student’s Perspective.

[15] Achieving the Dream, Holistic Student Supports.

[16] Council for Adult and Experiential Learning and Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, The Boost from PLA. Leibrandt, PLA from the Student’s Perspective. Wendy, Kilgore, An Examination of Prior Learning Assessment Policy and Practice as Experienced by Academic Records Professionals and Students (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, July 2020), accessed on 28 July 2020 at https://wiche.testing.brossgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/aacrao-brief071420.pdf.

References

Achieving the Dream. Holistic Student Supports Redesign: A Toolkit for Redesigning Advising and Student Services to Effectively Support Every Student. Silver Spring, MD: Achieving the Dream, October 2018. Accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://www.achievingthedream.org/sites/default/files/resources/atd_hss_redesign_toolkit_2018.pdf.

Advising Success Network. “About the Network.” Accessed on 29 July 2020 at https://www.advisingsuccessnetwork.org/about-the-network/.

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. “Today’s College Students.” Accessed on 9 January 2020 at https://postsecondary.gatesfoundation.org/areas-of-focus/our-policy-advocacy/advocacy-priorities/america-100-college-students/.

Council for Adult and Experiential Learning and Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education. The Boost from PLA: Results from a Targeted Study of Adult Student Outcomes. Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, forthcoming.

Donaldson, Joe and Steve Graham. “Model of college outcomes for adults.” Adult Education Quarterly, 50, no. 1 (November 1999). Accessed on 3 August 2020 at http://aeq.sagepub.com/content/50/1/24.full.pdf.

EDUCAUSE. “Planning for Rollout and Adoption: A Guide for iPASS Institutions.” Washington, DC: EDUCAUSE, 27 January 2017. Accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://library.educause.edu/resources/2017/1/planning-for-rollout-and-adoption-a-guide-for-ipass-institutions.

Fink, J. “How Does Access to Dual Enrollment and Advanced Placement Vary by Race and Gender Across States?” Community College Research Center, The Mixed Methods Blog, 5 November 2018. Accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/easyblog/access-dual-enrollment-advanced-placement-race-gender.html.

Giroir, Beth and Jeremy Schwehm. “Implementing Intrusive Advising Principles for Adult Learners in Online Programs.” NACADA Clearinghouse Resource, 24 April 2014. Accessed on 3 August 2020 at https://nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Clearinghouse/View-Articles/Implementing-Intrusive-Advising-Principles-for-Adult-Learners-in-Online-Programs.aspx.

Iten, Cindy and Albert Matheny. “Promoting Academic Advisors: Using a Career Ladder to Foster Professional Development at your Institution.” Academic Advising Today 31, no. 3 (2008). Accessed on 1 July 2020 at https://nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Academic-Advising-Today/View-Articles/Promoting-Academic-Advisors-Using-a-Career-Ladder-to-Foster-Professional-Development-at-Your-Institution.aspx.

Kalamkarian, Hoori, Karp, Melinda, and Elizabeth Ganga. What We Know About Technology-Mediated Advising Reform. New York, NY: Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University, February 2017. Accessed on 29 July 2020 at https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/what-we-know-technology-mediated-advising-reform.html

Kardash, Stacey M. “Holistic Advising.” NACADA Academic Advising Today, 26 May 2020. Accessed on 3 August 2020 at https://nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Academic-Advising-Today/View-Articles/Holistic-Advising.aspx

Kettler, Todd, and Luke Hurst. “Advanced Academic Participation: A Longitudinal Analysis of Ethnicity Gaps in Suburban Schools.” Journal for the Education of the Gifted 40, no. 1 (February 2017), 3-19. Accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353216686217

Kilgore, Wendy. An Examination of Prior Learning Assessment Policy and Practice as Experienced by Academic Records Professionals and Students. Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education. July 2020. Accessed on 28 July 2020 at https://wiche.testing.brossgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/aacrao-brief071420.pdf.

Leibrandt, Sarah. PLA from the Student’s Perspective: Lessons Learned from Survey and Interview Data. Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, forthcoming.

Lettman, Doug. “Identifying What’s Important for Adult Learners.” The Evolllution, 18 January 2017. Accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://evolllution.com/programming/program_planning/identifying-whats-important-for-adult-learners/.

Pardee, Celeste. “Organizational Models for Advising.” NACADA Clearinghouse of Academic Advising Resources, 2004. Accessed on 28 July 2020 at https://nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Clearinghouse/View-Articles/Organizational-Models-for-Advising.aspx

Theokas, Christina and Reid Saaris. Finding America’s Missing AP and IB Students. Washington, DC: The Education Trust, June 2013. Accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Missing_Students.pdf.

Tyton Partners. Driving Toward a Degree: Collaboration is Crucial to Holistic Student Supports. Washington, D.C.: NASPA Advising Success Network, 21 May 2020. Accessed on 3 August 2020 at https://www.advisingsuccessnetwork.org/foundational-context-and-planning/collaboration-is-crucial-to-holistic-student-supports-drivetodegree/

U.S. Government Accountability Office. Public High Schools with More Students in Poverty and Smaller Schools Provide Fewer Academic Offerings to Prepare for College. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Accountability Office, GAO-19-8, 2018. Accessed on 9 January 2020 at https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/694961.pdf.

About the Authors

- Alexa Wesley is an associate director for research and policy at NASPA – Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education, where she supports research and authors scholarship relating to student success and affordability. Prior to joining NASPA, Wesley served as a policy intern for Lumina Foundation, where she focused on federal postsecondary education policy and institutional finance. She also conducted policy research and provided support as an intern for the U.S. Department of Education and the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. She holds a B.A. in government and politics and a master’s degree in public policy from the University of Maryland, College Park.

- Amelia Parnell is vice president for research and policy at NASPA – Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education, where she leads many of the Association’s scholarly and advocacy-focused activities. Parnell writes and speaks frequently about topics related to student affairs, college affordability, student learning outcomes, and institutions’ use of data and analytics. Parnell’s policy and practitioner experiences include prior roles in association management, legislative policy analysis, internal audit, and TRIO programs. Her research portfolio includes studies of leadership in higher education, with a focus on college presidents and vice presidents and she is a co-editor of the book, The Analytics Revolution in Higher Education: Big Data, Organizational Learning, and Student Success. She currently serves on the board of directors for EDUCAUSE and is an advisor to several other higher education organizations. Parnell holds a Ph.D. in higher education from Florida State University and masters and bachelor’s degrees in business administration from Florida A & M University.

About the organization

- NASPA – Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education is the leading association for the advancement, health, and sustainability of the student affairs profession. NASPA provides high-quality professional development, advocacy, and research for 16,000 members in all 50 states, 25 countries, and 8 U.S. territories. Our guiding principles of Integrity, Innovation, Inclusion, and Inquiry shape our work of fulfilling the promise of higher ed for every student.

Copyright

Copyright © 2020 by the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education

3035 Center Green Drive, Boulder, CO 80301-2204

An Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer

Printed in the United States of America

Publication number 4a500125

Disclaimer

This publication was prepared by Alexa Wesley and Amelia Parnell of NASPA – Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Lumina Foundation, its officers, or its employees, nor do they represent those of Strada Education Network, its officers, or its employees.