Recognition of Learning TOC

Key Highlights of this Brief

- States, institutions, and the federal government can play a critical role in making credit for prior learning more accessible and affordable for students with low incomes, students of color, immigrants, and adult learners.

- Creating greater awareness of prior learning policies can help to increase college completion among students with low incomes, students of color, immigrants, and adult learners.

- State and system-level higher education policymakers and institutions must work to make prior learning policies transparent and available to students, faculty, and staff.

- State policymakers and higher education systems should consider expanding other acceptable forms of prior learning credit that recognize college-level learning from a variety of contexts, including learning that is gained from civic engagement, service learning, work-based learning, community-based social justice projects, and other unique and valuable experiences that are not typically considered for PLA; experiential learning should be valued and acknowledged by policymakers and educational

- While a one-size-fits-all state or federal PLA policy would not work for all states, systems, and institutions, PLA policies should be equitable and benefit all students.

Introduction

The recognition of prior learning occurs in a complex environment, affected by institutional policies, practices, and business models, as well as a complicated state and federal policy landscape. Many current and future students have acquired a great deal of college-level learning through their day-to-day lives outside of academia: knowledge acquired from work experience, such as on-the-job training, formal corporate training, training through non-corporate employers like government or nonprofit employers, military training, apprenticeships, and volunteer work; knowledge gained from civic engagement and service learning, community-based social justice projects, and self-study, and myriad other extra-institutional learning opportunities available through low-cost or no-cost online sources. Students can earn credit for this learning through a process commonly known as Prior Learning Assessment (PLA). The concept of PLA has been around since World War II and the G.I. Bill when postsecondary institutions began thinking of ways to help military veterans earn academic credit for their military experiences.[1] In the 1970s, incumbent workers and military veterans saw a further increase in opportunities to earn credit for their prior experiences.[2] In recent decades, PLA has also been largely associated with high-achieving high school students who have had opportunities to access AP and IB courses and receive credit for prior learning when they enter college.

As demographics of postsecondary students continue to shift and the nation’s colleges and universities continue to enroll greater numbers of students who do not meet the profile of the traditional college students entering college directly from high school, PLA policies and practices must be more inclusive of the types of learning and work-based experiences that students of color, students with low incomes, immigrants, and adult learners bring to the classroom. The nation’s higher education system is more racially and ethnically diverse than ever before, with students of color comprising nearly half of all undergraduates. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic crisis, 64 percent of students worked while in college (including 40 percent working full time), 37 percent are over the age 25, and a quarter are parents.[3] Adult working students, who are likely to have experience that meets the college-level learning standard, and who must balance work, school, and family obligations can benefit greatly from credit for prior learning to complete their postsecondary credentials.

Types of Prior Learning Assessment

Many students – as well as potential students – have acquired a great deal of college-level knowledge and skills through their day-to-day lives outside of academia: from work experience, on-the-job training, formal corporate training, military training, volunteer work, self-study, and myriad other extra-institutional learning opportunities available through low-cost or no-cost online sources.

The process for recognizing and awarding credit for college-level learning acquired outside of the classroom is often referred to as Prior Learning Assessment (PLA). There are several ways students can demonstrate this learning and earn credit for it in college. The various partners involved in creating this series of briefs are examining different types of PLA and using the following general descriptions of the different methods.

- Standardized examination: Students can earn credit by successfully completing exams such as Advanced Placement (AP), College-Level Examination Program (CLEP), International Baccalaureate (IB), Excelsior exams (UExcel), DANTES Subject Standardized Tests (DSST), and others.

- Faculty-developed challenge exam: Students can earn credit for a specific course by taking a comprehensive examination developed by campus faculty.

- Portfolio-based and other individualized assessment: Students can earn credit by preparing a portfolio and/or demonstration of their learning from a variety of experiences and non-credit activities. Faculty then evaluate the student’s portfolio and award credit as appropriate.

- Evaluation of non-college programs: Students can earn credit based on recommendations provided by the National College Credit Recommendation Service (NCCRS) and the American Council on Education (ACE) that conduct evaluations of training offered by employers or the military. Institutions also conduct their own review of programs, including coordinating with workforce development agencies and other training providers to develop crosswalks that map between external training/credentials and existing degree programs.

While other briefs in this series focus on the institutional policies and practices of prior learning assessment,[4] this brief highlights federal, state, and accreditation policies related to PLA. This brief first summarizes findings from previous state policy scans and then offers suggestions for how policies can better support students of color, students with low incomes, immigrants, and adult learners by addressing issues of transparency, affordability, inclusion, and evaluation. This brief concludes with recommendations for policymakers and accreditors and ideas for future research.

Previous summaries of PLA state policy

Experts in the field of PLA have conducted detailed landscape scans of state- and system-level policies regarding prior learning assessment in the last several years. For example, Education Commission of the States (ECS) conducted a 50-state scan in which they include references to states that have policies and statutes related to PLA.[5] HCM Strategists and the Council for Adult and Experiential Learning (CAEL) created a resource guide for state leaders considering drafting and implementing state policy.[6] Most recently, Jobs for the Future and CAEL drafted a series of memos for the California Community College System (CCCS) PLA taskforce that informed the CCCS PLA policy that was established in March 2020.[7] From these scans, we find that:

- 35 states and DC have system-level, state-level policy and/or legislation passed that requires institutions to award credit for military experience (31 of those states and the District of Columbia have passed legislation regarding credit for military experience).[8]

- 26 states have system-level, state-level policy and/or legislation that requires postsecondary education institutions to accept credit for minimum AP scores (four of those states have passed legislation regarding credit for minimum AP scores).[9]

- 27 states have system-level, state-level policy and/or legislation that requires institutions to award credit for prior learning outside of military and/or AP experience (10 of those states have passed legislation regarding credit for prior learning).[10]

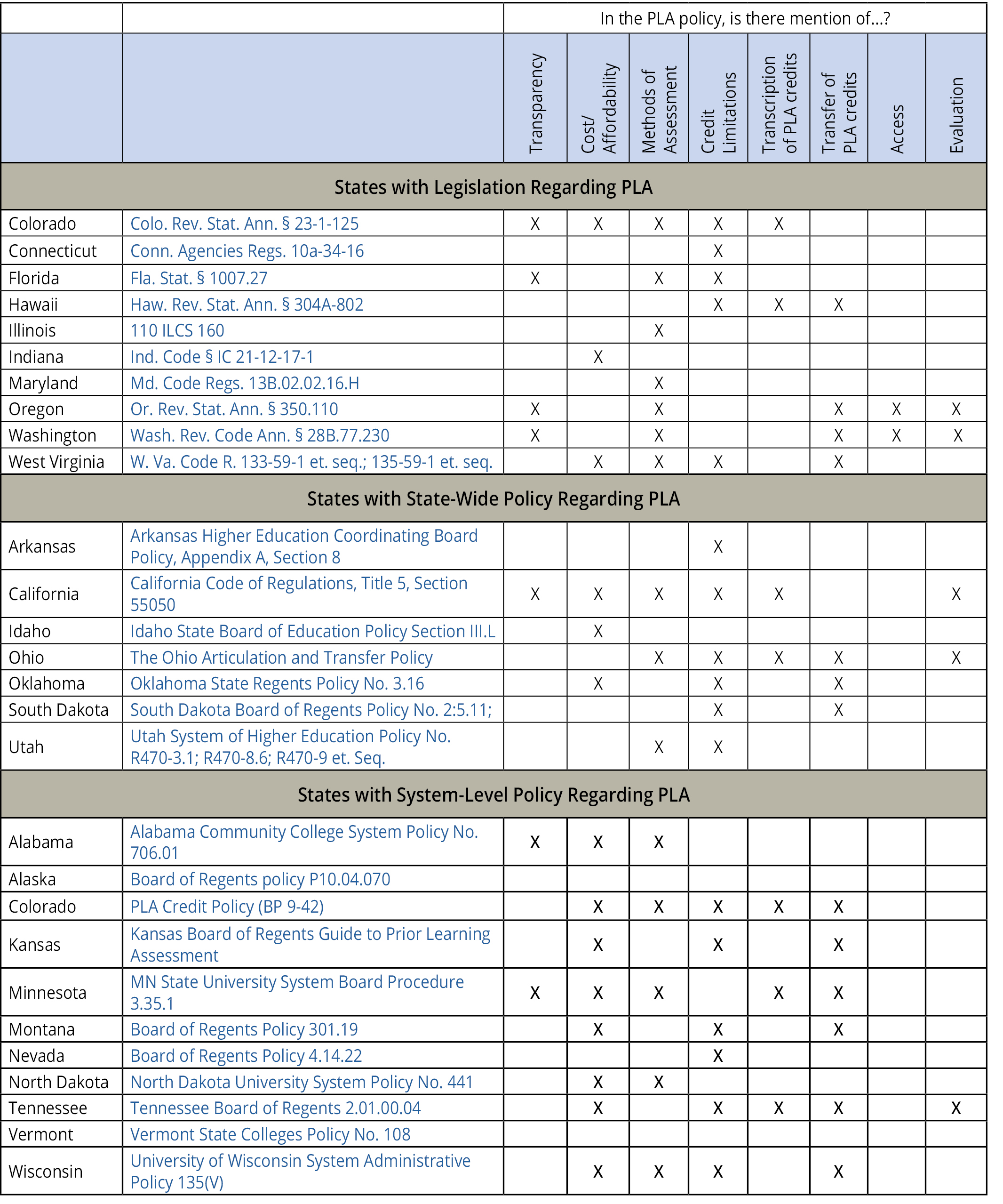

State PLA policy varies across states as it relates to creating a policy, making policies transparent, fees and costs, which assessment methods to include, credit limitations, articulation and transfer of PLA credit, evaluation/quality assurance, and capacity building (see Table 1). The above-mentioned sources offer multiple state examples for states to consider. We provide a few examples here:

- Transparency: Oregon statute requires the Higher Education Coordinating Commission to work with institutions to … “Develop transparent policies and practices in awarding academic credit for prior learning to be adopted by the governing boards of public universities, community colleges and independent institutions of higher education.”[11]

- Cost and affordability: West Virginia statute requires state colleges and universities to develop a policy in which “Prior Learning Assessment fees may vary based upon the type of assessment performed. Prior Learning Assessment credit and transcripting fees to students must be clearly published and available to the student.”[12] Indiana statute allows students to use state financial aid dollars toward the costs associated with PLA: “A recipient of a [state] grant, scholarship, or remission of fees … may use the funds from the grant, scholarship, or remission of fees to pay for costs associated with a prior learning assessment that the student attempts to earn during the academic year in which the student receives the grant, scholarship, or remission of fees if the prior learning assessment: (1) has been approved by the commission; and (2) costs not more than fifty percent (50%) of the full tuition and fees for an equivalent number of credits at Ivy Tech Community College of Indiana.”[13]

- Methods of assessment and types of PLA accepted: Connecticut state statute informs institutions; it states: “Acceptable methods of assessment include (A) standardized tests, (B) nationally recognized evaluations for credit recommendations accepted by the Board, (C) individualized written or oral tests designed and administered by qualified faculty, and (D) portfolio review.”[14]

- Credit limitations: West Virginia statute requires institutions to develop their own PLA policy in which, “credit for prior learning can apply toward majors, minors, general education requirements, and electives that count toward the student’s chosen degree or certificate. Prior Learning Assessment credit may also satisfy prerequisite requirements. College credit awarded through PLA shall not be treated differently in its application and use than its course equivalencies or appropriate block credit.”[15]

- Transcription of PLA credits: Connecticut statute requires institutions that award PLA credit maintain “comprehensive records of evaluations and credit decision …The records shall specify the experience for which credit was awarded, the method(s) of assessment, the names and titles of faculty members and administrators who recommended approval of credit, and the number of credits awarded. Sufficient information shall be entered on the student transcript, or attached to it, to enable registrars at other institutions or employers to understand the basis for the award of credit.”[16]

- Access: Washington statute requires institutions and systems to collaborate in PLA policy development to “Increase the number of students who receive academic credit for prior learning and the number of students who receive credit for prior learning that counts toward their major or toward earning their degree, certificate, or credential, while ensuring that credit is awarded only for high quality, course-level competencies.”[17]

- Evaluation: Oregon statute requires institutions and systems to “Develop outcome measures to track progress on the goals [regarding PLA access] outline [in the statute].”[18]

Table 1. PLA Policy

Data for Table 1 comes from Whinnery, “50-State Comparison: Prior Learning Assessment Policies”; Sherman and Klein-Collins, State Policy; Success Center for California Community Colleges, Credit for Prior Learning. In addition to the policies cited in these resources, Indiana State Statute (Ind. Code § IC 21-12-17-1) was established in 2017, California Community College Policy (Title 5, Section 55050) was established in 2020.

Similar themes emerge from previous policy scans: the importance of engaging stakeholders (whether faculty, college administrators, or legislative staff) at some level in the design and implementation of the policy; obtaining buy-in and campus-wide knowledge so that when the program is implemented there can be momentum and sustainability; determining who will administer the PLA program (one institution, program, or office to administer the PLA program system-wide, or administered separately at each institution within a system); clarifying which PLA methods are accepted; and attempting to make the process transparent.

These state policy scans also make evident some challenges to implementing statewide PLA policies: difficulties in implementing a statewide strategy without a dedicated staff person; lack of awareness among institution faculty and staff; determining the costs of PLA fees and who pays those fees; uncertainty of the ability for transcription PLA credits to be accepted at another institution, system, or state; and determining whether PLA will be noted on transcripts vs. student information systems.

Despite similarities among states regarding their PLA policies, most policies differ from each other (with the exception of Washington and Oregon statutes on PLA, which are mirror images of each other) due to state context. Some state statutes such as those in Hawaii and Illinois, while requiring institutions to implement PLA policies, offer little guidance to institutions as to what should go in said policy. Other states such as Oregon and Washington and systems such as the California Community College System offer institutions more detailed guidance in creating and implementing their PLA policies. Thus, the state examples found in these resources as well as the links in Table 1 to the actual policies will be helpful to any policymakers considering crafting and implementing state policy and legislation.

Findings

This brief contributes to the field by reviewing current state- and system- level PLA policies and practices through the lens of how those policies help to promote equity for students with low incomes, students of color, adult working students, and immigrant youth in postsecondary education. In the following sections, we consider the ways in which policies can scale up and improve prior learning by addressing issues of transparency, affordability, inclusion, and accessibility.

Transparency

Recent research from CAEL and WICHE suggests that just one in 10 adult students (at 72 institutions studied) earn PLA credit.[19] Nearly 40 percent of those institutions had adult student PLA take-up rates under 3 percent, and take-up rates for Black students and adult students with low incomes lagged take-up rates for other student subgroups.[20] One barrier to broader PLA usage is the lack of awareness about PLA among institution staff and students.[21] A key question to consider is: Even if students have PLA-eligible experiences, how can they take advantage of this opportunity if they are unaware of the opportunity to earn credit for those experiences? This is a policy area that has been the focus of federal, state, and accreditor PLA policies.

The U.S. Department of Education has recently attempted to address the issue of awareness by including prior learning assessment in the 2018 Negotiated Rulemaking process. The rulemaking committee agreed to proposed regulations that require any institution with a PLA policy to publish “written criteria used to evaluate and award credit for prior learning experience including, but not limited to, service in the armed forces, paid or unpaid employment, or other demonstrated competency or learning.”[22] These regulations went into effect on July 1, 2020.

Similar to this federal regulation, the seven institutional accrediting bodies (that formerly were classified as regional accrediting agencies) have requirements or make recommendations to institutions regarding the need to clearly communicate PLA policies to students, and those vary by accreditor. The New England Association of Schools and Colleges (NEASC) requires that PLA policies are “clearly stated and available” to students.[23] Other accrediting bodies leave communicating PLA policies to students as a suggestion for institutions to include. For example, Middle States Commission on Higher Education (MSCHE) acknowledges that PLA policies will vary across institutions and only suggests that communication of PLA policies is “clear and effective.”[24]

Even with accreditation mandates and recommendations that institutions make information about prior learning credit available to students, this does not always seem to happen. For example, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC) requires that institutions publish policies for credit “not originating from the institution.” In a 2018 study conducted by SACSCOC, however, many institutions reported that their policies aren’t actually that available to students: “The policy is not currently posted online”; “Kept in Registrar’s office”; “A more specific procedure and application is available in the Admissions office but not online.”[25] These responses illustrate how widely institutions, which follow the same regional accreditation recommendations, vary in terms of placement and level of transparency of PLA policies.

Many states require institutions to make PLA policies transparent for institution staff and students. As examples, Oregon statute requires that the policy is “transparent,”[26] and Hawaii statute requires that PLA policy is “made public.”[27] However, many of these state policies are limited to making information available for only military PLA. Although not a statewide policy, some systems such as the State Board for Community Colleges and Occupational Education in Colorado do have written policies regarding publicizing PLA opportunities, “Students have the right to clear and concise information concerning how [PLA] might help them reach their academic goals.”[28]

The federal government, state governments, and accreditors generally recognize (the three entities that make up higher education’s quality assurance triad)[29] that it is difficult for students to find out about PLA. Yet, the majority, if not all, of the policies in this area are related to notification. Notification or publication of information alone does not seem to be enough if the findings on PLA usage from the CAEL/WICHE study are any indication. Indeed, another brief in this series reports on findings from a survey of 1,100 current college students, 500 of whom had PLA-eligible experiences that suggest students learn about PLA most often from individual connections (to advisors, employers, peers, family members).[30] All levels of the triad need to better understand how well their policies regarding PLA transparency work and how students find out about PLA policies and programs. Without transparent, easy-to-find policies, many students with credit-eligible experiences but without the cultural capital to navigate the process for getting credit will continue to miss out on that opportunity.

Affordability

Another potential barrier to PLA is the cost to institutions and to students.[31] Institutions expend resources to assess prior learning, whether by developing and administering exams, evaluating portfolios, or consulting third-party credit recommendation guides.[32] Institutions often require students to carry some of these costs through fees.[33] However, oftentimes these fees are not eligible for financial aid. This potentially adds another large barrier for students unable to pay out-of-pocket for PLA opportunities. This is an area of policy that needs more attention by state and federal policymakers.

At the federal level, some members of Congress are cautious about making policy changes that cost money and have the potential to increase federal appropriations. While there is an appetite among federal lawmakers to increase persistence and completion rates for students with low incomes and students of color, current financial aid regulations do not consider the fees associated with the assessment of prior learning to be eligible for Title IV federal financial aid, which means that students must shoulder the cost of credit for prior learning credits.[34]

Yet, in 2014, the U.S. Department of Education included the option of using federal financial aid to cover PLA costs as part of the experimental sites program. According to the Federal Register Notice, this experiment would allow a handful of institutions to add PLA costs to the student’s overall cost of attendance, which would then factor into their federal financial aid calculation.[36] Second, the limited program would cover an additional three credits for student efforts to prepare materials for assessments.[37] These alternative methods have the potential to better support students in earning PLA by lowering the cost.

In 2017, CAEL conducted a review of the participating institutions. Nine of the 17 institutions that CAEL was able to reach indicated they had made some or full progress in implementing the experiment and report that the regulatory waivers permitted through the experiment made it easier for more students to successfully use this alternative pathway to credit-earning.[38] While students were able to save on cost of attendance, some institutions reported to CAEL that they had difficulty implementing the experiment because their student information system had a hard time tracking unique financial aid cases.[39]

The U.S. House of Representatives held five hearings in 2019 related to the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act. The fifth hearing, titled “Innovation to Improve Equity,” included discussion of competency-based education, a topic similar to PLA. Congressional testimony suggested that “We must ensure that programs offering learning beyond the traditional classroom provide students with the flexibility to learn at their own pace.”[40] Yet, as of 2020, PLA has not been featured in any drafts of the pending reauthorization of the Higher Education Act.

The cost of PLA is usually set by system or institution policy with some input from state policy in some cases. Only one state offers state financial aid to cover the costs of PLA. In 2017, Indiana passed legislation that allows students to use state financial aid award dollars to “pay for costs associated with a PLA that the student attempts to earn during the academic year in which the student receives the grant, scholarship, or remission of fees.”[41] Some state systems have PLA policies or statutes offering guidance to institutions on the cost of PLA. For example, the California Community Colleges system allows individual institutions or districts to determine the fee amount (up to the enrollment fee of a similar course).[42] Other systems such as the Colorado Community College System (CCCS) set the fee schedule across the state. CCCS mandates that there be no fee other than the testing fee for standardized exams, no fee for the transcript evaluation of the published guide, $45 fee per credit for a challenge exam, and $65 fee per credit for portfolio assessment.[43]

The seven institutional accrediting bodies (that formerly were classified as regional accrediting agencies) and federal government do not prescribe any set policy for PLA cost or fees. Outside of the experimental sites initiative, federal financial aid is not available to students earning PLA. This is particularly troubling as the U.S. recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic that started in early 2020. Without policies in place that allow students to use financial aid to pay for PLA, students without the financial means will continue being unable to take advantage of PLA. If not all students can benefit from PLA because they cannot afford to access it, then PLA becomes a means of reinforcing inequality in higher education.

Equity and Inclusion

A third barrier to accessing PLA for some students is the types of credit-eligible experiences that are accepted. Stephanie Fenwick, an adult educator and scholar, challenges the traditional definitions of “learning” and argues that PLA could serve as a way to foster inclusive excellence.[44] To consider a more inclusive definition of “learning,” through an equity-minded framework, “there must be a shift in understanding within traditional academia that gives serious weight to both experiential knowledge and diverse ways of knowing.”[45]

States and higher education governing boards vary in their credit for prior learning policies as previously mentioned. While an increasing number of states are adopting PLA policies, many of these policies primarily award credit for military service and AP/IB courses.[46] Fewer states allow credit for other work-based learning and service learning, but the emphasis continues to be on military service and training. In light of changing contexts, there is an opportunity here for states to reexamine their PLA policies.

PLA Policies and Legislation Regarding Military Experience

The majority of states have passed legislation directing state higher education agencies, system offices, or institutions to recognize the college-level learning that takes place in the military.[47] Some state statutes such as Indiana and Utah require institutions to create policies that provide credit to military personnel and veterans for their experiences while other state statutes such as those in Texas and Illinois only ask that boards “examine what might be the best process for awarding credit.”[48]

The American Council on Education validates college-level credit recommendations for military training, workplace learning, and civilian training and provides open source databases through online guides. These evaluations are rigorous, hands-on, in-depth assessments conducted by a team of teaching faculty from relevant academic disciplines, representing various colleges and universities. Faculty evaluators review military training and occupations, as well as training and exams for a variety of businesses and industries through the CREDIT® program.[49] For more information on the ACE credit recommendation process, see the forthcoming brief in this series written by ACE.[50]

In the recent study by CAEL and WICHE, adult PLA credit earners were most likely to earn credit through ACE military recommendations (68 percent of adults with PLA credits) compared to credit for corporate training through ACE/NCCRS (3.6 percent).[51] If the evaluation process is the same for college-level learning acquired through either the military or corporate training, and the majority of states have state policies to recognize college-level learning that takes place in the military as recommended by ACE, it follows that learning evaluated through a similar process ought to be recognized for credit as well.

While faculty members can play a key role in advancing greater equity for students and workers of color by recognizing the diversity of learners and their experiences in PLA policies on campus,[52] recent findings suggest few faculty members are aware of PLA and/or involved in creating PLA policy on campus.[53] A research study of over 400 community college faculty members in Texas found that “despite 2011 Texas state legislation (SB 1736) requiring state agencies and public institutions to adopt and expand methods for recognizing and awarding PLA credit, only 13% of [the faculty] surveyed for this study reported any formal training or professional development related to PLA.”[54]

In addition, some states and accrediting bodies have restrictive policies that limit the number of credits that can be awarded for prior learning, even though college costs continue to rise, and students may have already mastered the subject area and the courses they are being required to take to graduate.[55]

Despite these challenges, the awareness and potential impact of credit for prior learning policies on racial and economic justice is growing. Research by CAEL and WICHE shows PLA receipt is associated with a 17 percent increase in the likelihood of completing a credential, including a 24 percent increase for Latino students and 15 percent improvement for Black students.[56] With regard to majors and careers focused on social justice work in communities with low incomes, one PLA advocate and researcher notes that “there is a growing awareness that learning from experience, gained in a variety of contexts, including work, politics, and civics, should be more substantially acknowledged and rewarded, especially in educational institutions.”[57]

For example, Salish Kootenai College, a tribal college in Pablo, Montana, has a long history of awarding credit for prior learning of the Salish language. The native language teaching/apprenticeship program at Salish Kootenai not only honors elder knowledge and validates their traditional ways of learning, but also increases the capacity of the community to perpetuate the Salish language for younger generations. At the end of the program, students earn an associate’s degree in education and are eligible for Montana’s Class 7 teacher certification.[58]

Federal and state policymakers and educational institutions must recognize that these types of prior learning experiences help to lift individuals and communities out of poverty.

Access

Issues related to systemic racism in higher education present fourth barrier to accessing PLA for some students. Of great concern is research showing that Black students, American Indian/Alaska Native students, and students with low incomes are the least likely groups of students to take advantage of PLA opportunities.[59] State and federal policymakers and accreditors can use PLA as a policy lever to promote equity by understanding why some students but not others access and use PLA opportunities and then rectifying this disparity. In recent years, researchers have investigated why this disparity exists.

SUNY Empire State College faculty researchers heard from students who participated in their women-of-color PLA workshop series reasons why they don’t attempt to earn PLA:

Students reported that they routinely experience a range of micro-aggressions both within and outside our own academic setting, most often connected to race, but sometimes also to gender. Moreover, they noted that their experience with micro-aggressions affected their ability to value their knowledge and, even when they did value it, to submit it to institutional authority, and the threat of invalidation, through the PLA process.[60]

Another study, which focused on Latino students, PLA, and student outcomes, found that the marketing of PLA opportunities with messages such as “prove what you know” and “demonstrate what you have learned” can be a hurdle for students who are first in their families to attend college.[61] These reasons are not unique to PLA programs; rather these access issues are representative of systemic racism that has been prevalent in higher education for a long time.

The State Policy Approaches to Support Prior Learning Assessment guide highlights examples of states with policies aimed at improving student participation in PLA.[62] For example, Oregon and Washington’s state statute requires that the Higher Education Coordinating Commission create an advisory group to ensure the state is increasing PLA participation.[63] These two policies also include setting and achieving a benchmark goal in PLA participation.[64]

Faculty members and institution staff (such as academic advisors) can play a key role in increasing PLA participation and advancing greater equity for students and workers of color by recognizing the diversity of learners and encouraging them to earn PLA for college-level learning gained outside the classroom.[65] Yet, recent findings suggest few faculty members are aware of PLA and/or involved in creating PLA policy on campus.[66] A research study of over 400 community college faculty members in Texas found that “despite 2011 Texas state legislation (SB 1736) requiring state agencies and public institutions to adopt and expand methods for recognizing and awarding PLA credit, only 13% of [the faculty] surveyed for this study reported any formal training or professional development related to PLA.”[67] In an attempt to build capacity among faculty and staff to promote PLA opportunities, Oregon and Washington’s state statutes on PLA require that institutions “create tools to develop faculty and staff knowledge and expertise in awarding academic credit for prior learning and to share exemplary policies and practices among institutions of higher education.”[68] More research needs to be done to evaluate the efficacy of these (and other) PLA policies.

The policy guide written by the Success Center for California Community Colleges offers suggestions for how California might consider evaluating its PLA policy and includes examples from other states that do so. But notably, the guide does not include evaluation of student outreach, participation, and success disaggregated by race/ethnicity and income status, and an investigation of why and how there might be differences among student groups.

State policies should require institutions to regularly evaluate their PLA policies and programs. Institutions should ask themselves: are their PLA marketing campaigns reaching students, particularly students with low incomes and students of color? Are there professional development opportunities for faculty and staff to learn about PLA? Are these opportunities effective? How can PLA programs improve student participation and success among students of color and students with low incomes? Evaluations should include both quantitative and qualitative data to better understand the how and the why of these questions. State policies should also require institutions to include a strong advising component to their PLA programs, in which students can be individually coached and shown that they are in fact worthy of having their college-level learning validated at their institution.

Recommendations

PLA opportunities benefit students by saving them time and money and helping them finish what they have started. [69] PLA also benefits institutions. For example, the CAEL and WICHE study found that adult students with PLA earned, on average, 17.6 more regular residential credits than the adult students without PLA credit. [70] In other words, on average, institutions earned roughly a full-time semester’s worth of additional tuition revenue from adult students with PLA compared to adult students without PLA. As institutions face tightened budgets and less revenue due to COVID-19, institutions would find value in implementing or bolstering their PLA programs, and states should support their institutions in doing so.

When considering what components to include in a state policy, states can look to their peers and to state policy reference guides for examples. State approaches vary, from being prescriptive to suggestive in different aspects of PLA policy including transferability, credit limitations, capacity building, transparency, and more. To help ensure PLA policy and practice help reduce inequity among the students who are trying to access and benefit from PLA, this brief has looked at how state and federal policymakers and accreditors consider issues such as transparency, cost of PLA, types of PLA offered, and evaluation.

Higher education governing systems and the socio-, political-, and economic-context of each state are unique. So, to be clear, there cannot be a one-size-fits-all state or federal PLA policy that would work for all states, systems, and institutions. But it would behoove policymakers to consider the following recommendations as they draft, implement, and improve their PLA policies to ensure PLA policies are equitable and benefit all students. If these recommendations are implemented, institutions and states should conduct adequate evaluation and research to make sure that the changes are doing what they were intended to do. In doing so, more students will be able to access and benefit from PLA.

The most effective PLA policies will address four key areas:

Transparent.

- Institutions should make campus policies clear and transparent to institutional staff and students.

- Institutions should ensure that all students understand the opportunities available to them through PLA.

- Institutions should conduct policy and program evaluations regularly using quantitative and qualitative data to better understand how students are notified about PLA opportunities and which notification methods work the best for increasing access to PLA.

- Institutions and states should ensure that the new federal regulation requiring institutions to publicize PLA policies increases awareness among students through evaluation and review.

Affordable.

- Federal and state financial aid policies might consider allowing PLA costs to be covered by aid; this will ensure that access to PLA is not limited by cost.

- Institutions and states should re-examine the business case for PLA. Students who earn PLA are more likely to enroll in additional classes, which means higher enrollments, increased state support and the potential for higher completion rates for an institution. Institutions might consider covering some of the costs of PLA (such as fees) as a “loss leader.”

Inclusive.

- States that mandate acceptance of credit based on recommendations for military training should consider also mandating acceptance of credit based on recommendations for corporate training because that college-level learning is evaluated with the same process.

- States, systems, and institutions should consider expanding other acceptable forms of learning credit in their PLA policy that recognize experiential learning from a variety of contexts: social-justice work-based learning experiences, registered apprenticeships, civic engagement, service learning, and others. These learning experiences could help students with low incomes, students of color, immigrants, and adult learners succeed in school and the workforce, and can benefit their communities.

Reflective.

- States and institutions should review existing PLA policies for issues related to equity – ensure that the wording and implementation of policies are equitable.

- Institutions should conduct evaluations to understand what take-up rates look like at institutions that use multiple vehicles (such as on the website, in electronic communication materials with students, etc.) to provide information about prior learning as compared to take-up rates at institutions that don’t publicize PLA as widely.

- States should conduct analyses to compare PLA take-up rates across institutions. Are students with low incomes, students of color, immigrant students, and adult learners participating? Are there disparities in access? If so, find out why.

Future Directions

More research is needed on the impact of PLA policies and programs on student outcomes, including positive outcomes related to college affordability and completion for students with low incomes, students of color, immigrants, and adult learners. Given that each state has a unique political, social, economic, and geographic makeup, in what state contexts do PLA policies seem to succeed? What do these PLA policies look like?

Furthermore, while several studies have looked at the types of credit-eligible experiences of students and their usage and success in earning PLA credit, we encourage more research on social-justice types of work-based learning experiences and registered apprenticeships as an acceptable form of prior learning credit and the impact they can have on students with low incomes, students of color, immigrants, and adult learners. What types of experiences do students have and how are they earning credit for these credit-eligible experiences?

Conclusion

The federal government, states, and institutions can employ various strategies to support success for historically underrepresented students. In other parts of the world, such as South Africa, PLA has been viewed as a vehicle to seek redress and to promote social justice for workers and students who have been locked out of educational opportunities.[72] In the United States, PLA policies can be a potential policy lever to help support greater numbers of students with low incomes and students of color succeed in college and beyond. But without careful consideration of how students learn about and use PLA opportunities, PLA is just another process that requires privilege to access, and thus, just another means by which our systems will continue to produce inequitable outcomes. PLA policies that center racial equity, recognize work-based and experiential learning in various contexts, and ensure that institutional staff purposefully and proactively reach out to students of color and students with low incomes can help to promote economic security and social justice in communities.

As the face of postsecondary students continues to change, as states look to weather the impact of COVID-19, and as institutions look for new ways to support college affordability, student success, and racial and social justice, Congress, states, governing bodies, and institutions should view PLA as part of a much larger strategy to redesign the nation’s colleges and universities and do more to promote economic security and advance equity in postsecondary education and beyond.[73]

Endnotes

[1] Nan L. Travers, “What Is Next after 40 Years? Part 1: Prior Learning Assessment: 1970–2011,” Journal of Continuing Higher Education 60, no. 1 (2012): 43–47.

[2] Mary Beth Lakin, Deborah Seymour, Christopher J. Nellum, and Jennifer R. Crandall, Credit for Prior Learning, Charting Institutional Practice for Sustainability (Washington D.C.: American Council on Education, 2015), accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/Credit-for-Prior-Learning-Charting-Institutional-Practice-for-Sustainability.pdf.

[3] Lumina Foundation, Who is Today’s Student? (Indianapolis, IN: Lumina Foundation, 2019), accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://www.luminafoundation.org/resource/todays-student/.

[4] Wendy Kilgore, An Examination of Prior Learning Assessment Policy and Practice as Experienced by Academic Records Professionals and Students (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education), 2020; Heather A. McKay and Daniel Douglas, Credit for Prior Learning in the Community College: A Case from Colorado (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education), October 2020; Amelia Parnell and Alexa Wesley, Advising and Prior Learning Assessment for Degree Completion (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education), September 2020; Amy Goldstein, HBCUs and Prior Learning Assessments (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education), October 2020.

[5] Erin Whinnery, Education Commission of the States “50-State Comparison: Prior Learning Assessment Policies, 2017,” accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://www.ecs.org/50-state-comparison-prior-learning-assessment-policies/.

[6] Amy Sherman and Rebecca Klein-Collins, State Policy Approaches to Support Prior Learning Assessment (Chicago, IL: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, 2015).

[7] Success Center for California Community Colleges, Credit for Prior Learning, A Framework of Policy Components to Consider (Sacramento, CA: Success Center for California Community Colleges, 2019).

[8] Whinnery, “50-State Comparison”; Sherman and Klein-Collins, State Policy Approaches; Success Center for California Community Colleges, Credit for Prior Learning; Education Commission for the States, “Does the state have a policy to award academic credit for military experience? February 2018,” accessed on 1 October 2020 at http://ecs.force.com/mbdata/mbquest3rta?Rep=MIL.

[9] Education Commission of the States, “Advanced Placement – State postsecondary institutions must award credit for minimum scores, 2016,” accessed on 1 October 2020 at http://ecs.force.com/mbdata/MBQuestRT?Rep=AP1216.

[10] Whinnery, “50-State Comparison: Prior Learning Assessment Policies”; Sherman and Klein-Collins, State Policy; Success Center for California Community Colleges, Credit for Prior Learning; In addition to the policies cited in these resources, Indiana State Statute (Ind. Code § IC 21-12-17-1) was established in 2017, California Community College Policy (Title 5, Section 55050) was established in 2020.

[11] Or. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 350.110

[12] W. Va. Code R. 133-59-1 et. seq.; 135-59-1 et. seq.

[13] Ind. Code § IC 21-12-17-1

[14] Conn. Agencies Regs. 10a-34-16

[15] W. Va. Code R. 133-59-1 et. seq.; 135-59-1 et. seq.

[16] Conn. Agencies Regs. 10a-34-16

[17] Wash. Rev. Code Ann. § 28B.77.230; Note that Washington and Oregon state statute regarding PLA have almost identical language. For Oregon’s statute, see Or. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 350.110.

[18] Or. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 350.110

[19] Rebecca Klein-Collins, Jason Taylor, Carianne Bishop, Peace Bransberger, Patrick Lane, and Sarah Leibrandt, The PLA Boost: Results from a 72-Institution Targeted Study of Prior Learning Assessment and Adult Student Outcomes (Indianapolis, IN: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning), October 2020.

[20] Klein-Collins, Taylor, Bishop, Bransberger, Lane, and Leibrandt, The PLA Boost.

[21] Alexei Matveev, “Credentialing: An Exploratory Survey of Non-Credit to Credit Conversion Activities,” PowerPoint presentation, Atlanta, GA, 2018; Wendy Kilgore, An Examination of Prior Learning Assessment Policy and Practice as Experienced by Academic Records Professionals and Students (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, 2020) accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://wiche.testing.brossgroup.com/key-initiatives/recognition-of-learning/.

[22] Section 668.43 (c)(11)(iii) from Federal Registrar, The Daily Journal of the United States Government, Rule, “Student Assistance General Provisions, The Secretary’s Recognition of Accrediting Agencies, The Secretary’s Recognition Procedures for State Agencies,” 1 November 2019, accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/11/01/2019-23129/student-assistance-general-provisions-the-secretarys-recognition-of-accrediting-agencies-the.

[23] New England Commission of Higher Education, “Standards for accreditation,” accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://www.neche.org/resources/standards-for-accreditation/#standard_four.

[24] Middle States Commission on Higher Education, “Transfer Credit, Prior Learning, and Articulation,” accessed in 10 August 2020 at https://msche.my.salesforce.com/sfc/p/#46000000ZDJj/a/46000000XpsS/pbSE8DiFm.O2uwwgHKrizuVrATMFcHudkjKcdSFNyOA.

[25] Matveev, “Credentialing: An Exploratory Survey.”

[26] Or. Rev. Stat. § 350.110 (2020).

[27] Hawaii Rev. Stat. § 304A-802 (2012).

[28] Colorado Community College System, Policies and Procedures, “Policy BP 9-42 Prior Learning Assessment Credit,” accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://internal.cccs.edu/board-policies/bp-9-42-prior-learning-assessment-credit/; as cited in Success Center for California Community Colleges, Credit for Prior Learning, 21.

[29] The Higher Education Act (HEA) requires three entities to participate in regulating and ensuring quality in U.S. higher education: states, accreditation agencies, and the U.S. Department of Education; Higher Learning Advocates, “101: Higher Education and the Triad,” accessed on 28 October 2020 at https://higherlearningadvocates.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/higher-ed-and-the-triad.pdf.

[30] Sarah Leibrandt, PLA from the Student’s Perspective: Lessons Learned from Survey and Interview Data (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, forthcoming).

[31] Kilgore, An Examination of Prior Learning.

[32] Rebecca Klein-Collins, PLA Is Your Business: Pricing and Other Considerations for the PLA Business Model (Chicago, IL: Council for Adult and Experiential Education, November 2015), accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://www.cael.org/pla/publication/pla-is-your-business.

[33] Klein-Collins, PLA Is Your Business.

[34] Tucker Plumlee and Rebecca Klein-Collins, Financial Aid for Prior Learning Assessment: Early Successes and Lessons from the U.S. Department of Education’s Experimental Sites Initiative (Indianapolis, IN: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, 2017); U.S. House Committee on Education and the Workforce, “Keeping College Within Reach, Improving Higher Education Through Innovation: Hearing Before the Committee on Education and the Workforce, U.S. House of Representatives, 9 July 2013,” accessed on 7 August 2020 https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=eiP9siDOzmQC&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA1.

[35] Federal Student Aid, Office of the U.S. Department of Education, “Federal Register Notice, Invitation to Participate in the Experimental Sites Initiative, 31 July 2014,” accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://ifap.ed.gov/federal-registers/07-31-2014-subject-invitation-participate-experimental-sites-initiative.

[36] Federal Student Aid, “Federal Register Notice.”

[37] Federal Student Aid, “Federal Register Notice.”

[38] Plumlee and Klein-Collins, Financial Aid for Prior Learning Assessment.

[39] Plumlee and Klein-Collins, Financial Aid for Prior Learning Assessment.

[40] Robert C. Scott, “Innovation to Improve Equity: Exploring High-Quality Pathways to a College Degree,” Opening Statement for Full Committee Hearing in the U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Education and Labor, 19 June 2019, accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://edlabor.house.gov/imo/media/doc/2019-06-19%20RCS%20Innovation%20to%20Improve%20Equity%20Hearing%20Opening%20Statement3.pdf.

[41] Ind. Code § IC 21-12-17-1 (2019), accessed on 13 May 2020 at http://iga.in.gov/legislative/laws/2019/ic/titles/021/#21-12-17-1.

[42] Success Center for California Community Colleges, Credit for Prior Learning, 31; CA ADC § 55050.

[43] Fee structure for Colorado Community College System as described in the report, Success Center for California Community Colleges, Credit for Prior Learning, 30.

[44] Stephanie Fenwick, “Equity-Minded Learning Environments: PLA as a Portal to Fostering Inclusive Excellence,” Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 63, Issue 1, (Jan-Apr 2015): 51-58, accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07377363.2015.997378?needAccess=true&.

[45] Fenwick, “Equity-Minded Learning.”

[46] Whinnery, “50-State Comparison: Prior Learning Assessment Policies”.

[47] Whinnery, “50-State Comparison: Prior Learning Assessment Policies”; Sherman and Klein-Collins, State Policy Approaches.

[48] Sherman and Klein-Collins, State Policy Approaches, 11.

[49] American Council on Education, “CREDIT Evaluations,” accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://www.acenet.edu/Programs-Services/Pages/Credit-Transcripts/CREDIT-Evaluations.aspx.

[50] Dallas Kratzer, Louis Soares, and Michele Spires, Recognition of Learning Across Military and Corporate Settings: How ACE Blends Standard Processes, Disciplinary Expertise, and Context to Ensure Quality (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, forthcoming).

[51] Klein-Collins, Taylor, Bishop, Bransberger, Lane, and Leibrandt, The PLA Boost.

[52] Lakin, Nellum, Seymour, and Crandall, Credit for Prior Learning.

[53] Barra Chantel Reynolds, Faculty Perceptions of Prior Learning Assessment (Rapid City, SD: National American University, 2020).

[54] Reynolds, Faculty Perceptions.

[55] Whinnery, “50-State Comparison: Prior Learning Assessment Policies”; Furthermore, in the report written by Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, Holding Tight or At Arm’s Length: How Higher Education Regional Accrediting Bodies Address PLA (Indianapolis, IN: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, 2014), 7, accessed on 20 June 2020 at http://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/617695/premium_content_resources/pla/PDF/CAEL_PLA_Accreditation.pdf, three of seven accreditors placed limitations on the ways in which PLA credits can be treated internally. In 2020, one of the three, Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities, revised its policy on credit for prior learning. The new policy does away with the 25% threshold “in favor of higher education institutional best practices around credit for prior learning,” Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities, 2020 Standards for Accreditation and Eligibility Requirements Revision June 2019 Update (Redmond, WA: Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities, 2019), 22, accessed on 8 July 2020 at https://www.nwccu.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/NWCCUStandardsJuneUpdateFINAL2.pdf.

[56] Klein-Collins, Taylor, Bishop, Bransberger, Lane, and Leibrandt, The PLA Boost.

[57] Andy Mott, Prior Learning Assessments Help Students Earn College Credit, Community Learning Partnership, accessed on 10 November 2019 at http://communitylearningpartnership.org/prior-learning-assessment-can-help-students-earn-college-credit/.

[58] Montana Rule 10.57.436, “Class 7 American Indian Language and Culture Specialist,” accessed on 9 November 2020 at http://www.mtrules.org/gateway/ruleno.asp?RN=10%2E57%2E436; Salish Kootenai College, “Salish Language Educator Development (SLED) Program,” accessed on 9 November 2020 at https://www.skc.edu/sled/.

[59] Klein-Collins, Fueling the Race; Rebecca Klein-Collins and Richard Olson, Random Access: The Latino Student Experience with Prior Learning Assessment (Chicago, IL: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, 2014), 4; Milan S. Hayward and Mitchell R. Williams, “Adult Learner Graduation Rates at Four U.S. Community Colleges by Prior Learning Assessment Status and Method,” Community College Journal of Research and Practice 39, no. 1 (2015), 44-54; Heather McKay, Bitsy Cohn, and Li Kuang, “Prior Learning Assessment Redesign: Using Evidence to Support Change,” The Journal of Continuing Higher Education 64, no. 3 (2016); Klein-Collins, Taylor, Bishop, Bransberger, Lane, and Leibrandt, The PLA Boost.

[60] Kathy Leaker and Frances A. Boyce, “A Bigger Rock, a Steeper Hill: PLA, Race, and the Color of Learning,” The Journal of Continuing Higher Education 63, no. 3 (2015), 202.

[61] Klein-Collins and Olson, Random Access.

[62] Sherman and Klein-Collins, State Policy Approaches.

[63] Sherman and Klein-Collins, State Policy Approaches, 12.

[64] Sherman and Klein-Collins, State Policy Approaches, 12.

[65] Lakin, Nellum, Seymour, and Crandall, Credit for Prior Learning; Parnell and Wesley, Advising and Prior Learning Assessment for Degree Completion; Goldstein, HBCUs and Prior Learning Assessment; Reynolds, Faculty Perceptions.

[66] Reynolds, Faculty Perceptions.

[67] Reynolds, Faculty Perceptions.

[68] Wash. Rev. Code Ann. § 28B.77.230; Or. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 350.110.

[69] Klein-Collins, Fueling the Race; Klein-Collins, Taylor, Bishop, Bransberger, Lane, and Leibrandt, The PLA Boost; Kilgore, An Examination of Prior Learning; Heather A. McKay and Danial Douglas, Credit for Prior Learning in the Community College: A Case from Colorado (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education), forthcoming.

[70] Klein-Collins, Taylor, Bishop, Bransberger, Lane, and Leibrandt, The PLA Boost.

[71] Sherman and Klein-Collins, State Policy Approaches; Success Center for California Community Colleges, Credit for Prior Learning.

[72] Laurien Alexandre. Considering Prior Learning as a Valuable Pedagogy of Practice, unpublished report, n.d.

[73] Lakin, Nellum, Seymour, and Crandall, Credit for Prior Learning.

References:

American Council on Education. “CREDIT Evaluations.” Accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://www.acenet.edu/Programs-Services/Pages/Credit-Transcripts/CREDIT-Evaluations.aspx.

Colorado Community College System, Policies and Procedures. “Policy BP 9-42 Prior Learning Assessment Credit.” Accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://internal.cccs.edu/board-policies/bp-9-42-prior-learning-assessment-credit/.

Council for Adult and Experiential Learning. Holding Tight or At Arm’s Length: How Higher Education Regional Accrediting Bodies Address PLA. Chicago, IL: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, 2014. Accessed on 20 June 2020 at http://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/617695/premium_content_resources/pla/PDF/CAEL_PLA_Accreditation.pdf

Federal Registrar, The Daily Journal of the United States Government, Rule. “Student Assistance General Provisions, The Secretary’s Recognition of Accrediting Agencies, The Secretary’s Recognition Procedures for State Agencies, Section 668.43 (c), 1 November 2019.” Accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/11/01/2019-23129/student-assistance-general-provisions-the-secretarys-recognition-of-accrediting-agencies-the.

Federal Student Aid, Office of the U.S. Department of Education. “Federal Register Notice, Invitation to Participate in the Experimental Sites Initiative, 31 July 2014.” Accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://ifap.ed.gov/federal-registers/07-31-2014-subject-invitation-participate-experimental-sites-initiative.

Fenwick, Stephanie. “Equity-Minded Learning Environments: PLA as a Portal to Fostering Inclusive Excellence.” Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 63, Issue 1, (Jan-Apr 2015): 51-58. Accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07377363.2015.997378?needAccess=true&.

Hawaii Rev. Stat. § 304A-802 (2012).

Hayward, Milan S. and Mitchell R. Williams. “Adult Learner Graduation Rates at Four U.S. Community Colleges by Prior Learning Assessment Status and Method.” Community College Journal of Research and Practice 39, no. 1 (2015).

Hoffmann, Theresa and Kevin A. Michel. “Recognizing Prior Learning Assessment Best Practices for Evaluators: An Experiential Learning Approach.” Journal of Continuing Higher Education 58, no. 2 (2010): 113–120.

Ind. Code § IC 21-12-17-1 (2019). Accessed on 13 May 2020 at http://iga.in.gov/legislative/laws/2019/ic/titles/021/#21-12-17-1.

Kilgore, Wendy. An Examination of Prior Learning Assessment Policy and Practice as Experienced by Academic Records Professionals and Students. Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, 2020. Accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://wiche.testing.brossgroup.com/key-initiatives/recognition-of-learning/.

Klein-Collins, Rebecca, Jason Taylor, Carianne Bishop, Peace Bransberger, Patrick Lane, and Sarah Leibrandt. The PLA Boost: Results from a 72-Institution Targeted Study of Prior Learning Assessment and Adult Student Outcomes. Indianapolis, IN: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, October 2020.

Klein-Collins, Rebecca and Richard Olson. Random Access: The Latino Student Experience with Prior Learning Assessment. Chicago, IL: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, 2014.

Klein-Collins, Rebecca. Fueling the Race to Postsecondary Success. Chicago, IL: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, March 2010. Accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED524753.pdf

Klein-Collins, Rebecca. PLA Is Your Business: Pricing and Other Considerations for the PLA Business Model. Chicago, IL: Council for Adult and Experiential Education, November 2015. Accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://www.cael.org/pla/publication/pla-is-your-business.

Kratzer, Dallas, Louis Soares, and Michele Spires. Recognition of Learning Across Military and Corporate Settings: How ACE Blends Standard Processes, Disciplinary Expertise, and Context to Ensure Quality. Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, forthcoming.

Lakin, Mary Beth, Deborah Seymour, Christopher J. Nellum, and Jennifer R. Crandall. Credit for Prior Learning, Charting Institutional Practice for Sustainability. Washington D.C.: American Council on Education, 2015. Accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/Credit-for-Prior-Learning-Charting-Institutional-Practice-for-Sustainability.pdf.

Leaker, Kathy and Frances A. Boyce. “A Bigger Rock, a Steeper Hill: PLA, Race, and the Color of Learning.” The Journal of Continuing Higher Education 63, no. 3 (2015).

Lumina Foundation. Who is Today’s Student? Indianapolis, IN: Lumina Foundation, 2019. Accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://www.luminafoundation.org/resource/todays-student/.

Matveev, Alexei. “Credentialing: An Exploratory Survey of Non-Credit to Credit Conversion Activities.” PowerPoint presentation, Atlanta, GA, 2018.

McKay, Heather A. and Daniel Douglas. Credit for Prior Learning in the Community College: A Case from Colorado. Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, forthcoming.

McKay, Heather, Bitsy Cohn, and Li Kuang. “Prior Learning Assessment Redesign: Using Evidence to Support Change.” The Journal of Continuing Higher Education 64, no. 3 (2016).

Middle States Commission on Higher Education. “Transfer Credit, Prior Learning, and Articulation.” Accessed in 10 August 2020 at https://msche.my.salesforce.com/sfc/p/#46000000ZDJj/a/46000000XpsS/pbSE8DiFm.O2uwwgHKrizuVrATMFcHudkjKcdSFNyOA.

Mitchell, Ted. “Higher Education Fourth Supplemental Letter.” Accessed on May 7, 2020, https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/Letter-Senate-Higher-Ed-Supplemental-Request-040920.pdf.

Mott, Andy. Prior Learning Assessments Help Students Earn College Credit. Community Learning Partnership. Accessed on 10 November 2019 at http://communitylearningpartnership.org/prior-learning-assessment-can-help-students-earn-college-credit/.

New England Commission of Higher Education. “Standards for accreditation.” Accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://www.neche.org/resources/standards-for-accreditation/#standard_four.

Or. Rev. Stat. § 350.110 (2020).

Plumlee, Tucker and Rebecca Klein-Collins. Financial Aid for Prior Learning Assessment: Early Successes and Lessons from the U.S. Department of Education’s Experimental Sites Initiative. Indianapolis, IN: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, 2017.

Reynolds, Barra Chantel. Faculty Perceptions of Prior Learning Assessment. Rapid City, SD: National American University, 2020.

Scott, Robert C. “Innovation to Improve Equity: Exploring High-Quality Pathways to a College Degree.” Opening Statement for Full Committee Hearing in the U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Education and Labor, 19 June 2019. Accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://edlabor.house.gov/imo/media/doc/2019-06-19%20RCS%20Innovation%20to%20Improve%20Equity%20Hearing%20Opening%20Statement3.pdf.

Sherman, Amy and Rebecca Klein-Collins. State Policy Approaches to Support Prior Learning Assessment. Chicago, IL: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, 2015.

Success Center for California Community Colleges. Credit for Prior Learning, A Framework of Policy Components to Consider. Sacramento, CA: Success Center for California Community Colleges, 2019.

Travers, Nan L. “What Is Next after 40 Years? Part 1: Prior Learning Assessment: 1970–2011.” Journal of Continuing Higher Education 60, no. 1 (2012): 43–47.

U.S. House Committee on Education and the Workforce. “Keeping College Within Reach, Improving Higher Education Through Innovation: Hearing Before the Committee on Education and the Workforce, U.S. House of Representatives, 9 July 2013.” Accessed on 7 August 2020 https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=eiP9siDOzmQC&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA1.

Whinnery, Erin. Education Commission of the States. “50-State Comparison: Prior Learning Assessment Policies, 2017.” Accessed on 10 August 2020 at https://www.ecs.org/50-state-comparison-prior-learning-assessment-policies/.

Wihak, Christine and Emma Bourassa. Examining the Cultural Component of PLAR: Prior learning Assessment and Recognition for Distance Education Students in Myanmar. Oslo, Norway: Proceedings of the 2013 Annual Conference of the European Distance and E-Learning Network, 2013: 543–52.

Wong, Angela. “Recognition of Prior Learning and Social Justice in Higher Education.” In Handbook of the Recognition of Prior Learning Research into Practice, edited by Judy Harris, Christine Wihak, and Joy Van Kleef. England and Wales: The National Institute of Adult Continuing Education.

About the Authors

- Sarah Leibrandt is a senior research analyst at the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education. Since joining WICHE in 2013, Leibrandt has helped state agencies share education and workforce data with each other through the Multistate Longitudinal Data Exchange as a way to provide better information to students and their families while also improving education, workforce, and economic development policy. Currently, Leibrandt leads WICHE’s adult learner initiatives that include Recognizing Learning in the 21st Century, a large-scale research study and landscape analysis of the scaling of prior learning assessment policies and practices. Prior to joining WICHE, Leibrandt worked for the Colorado Department of Education and Red Rocks Community College. Leibrandt earned a bachelor’s degree from Wellesley College and a Ph.D. in Education Policy from the University of Colorado Boulder.

- Rosa M. García is director of postsecondary education and workforce development at the Center for Law and Social Policy. She works to expand access to postsecondary opportunities and career pathways for low-income students, educationally underprepared adults, students of color, and immigrants. Prior to joining CLASP, previous positions include Deputy Chief of Staff/Legislative Director to a senior member of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, Executive Director of Legislative Affairs at the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities (HACU), and a gubernatorial appointment to the Maryland State Board of Education. García earned her undergraduate degree at Wesleyan University and holds master’s degrees from Teachers College, Columbia University; the University of California at Los Angeles; and Baruch College, City University of New York. In 2015, she completed a Doctor of Education from the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education.

About the organizations

- For more than 65 years, the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) has been strengthening higher education, workforce development, and behavioral health throughout the region. As an interstate compact, WICHE partners with states, territories, and postsecondary institutions to share knowledge, create resources, and develop innovative solutions that address some of our society’s most pressing needs. From promoting high-quality, affordable postsecondary education to helping states get the most from their technology investments and addressing behavioral health challenges, WICHE improves lives across the West through innovation, cooperation, resource sharing, and sound public policy.

- The Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP) is a national, nonpartisan, anti-poverty nonprofit advancing policy solutions for low-income people. CLASP develops practical yet visionary strategies for reducing poverty, promoting economic opportunity, and addressing barriers faced by people of color. With over 50 years’ experience at the federal, state, and local levels, CLASP is fighting back in today’s threatening political climate while advancing our vision for the future.

Copyright

Copyright © 2020 by the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education

3035 Center Green Drive, Boulder, CO 80301-2204

An Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer

Printed in the United States of America

Publication number 4a500133

Disclaimer

This publication was prepared by Rosa García of Center for Law and Social Policy and Sarah Leibrandt of Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Lumina Foundation, its officers, or its employees, nor do they represent those of Strada Education Network, its officers, or its employees.